By Tereza Pultarova for Space.com

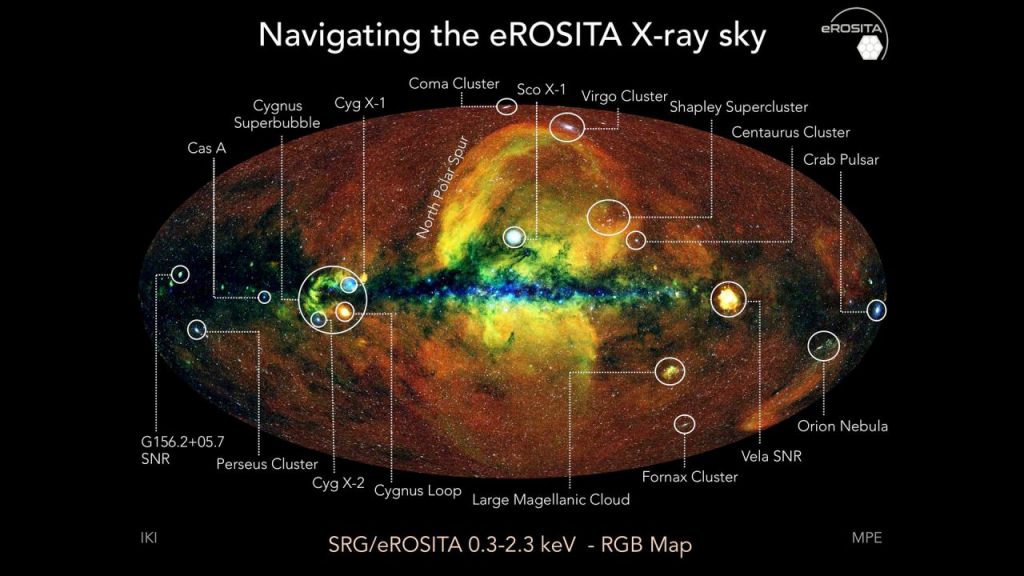

A German-built space telescope is creating the most detailed map of black holes and neutron stars across our universe, revealing more than 3 million newfound objects in less than two years.

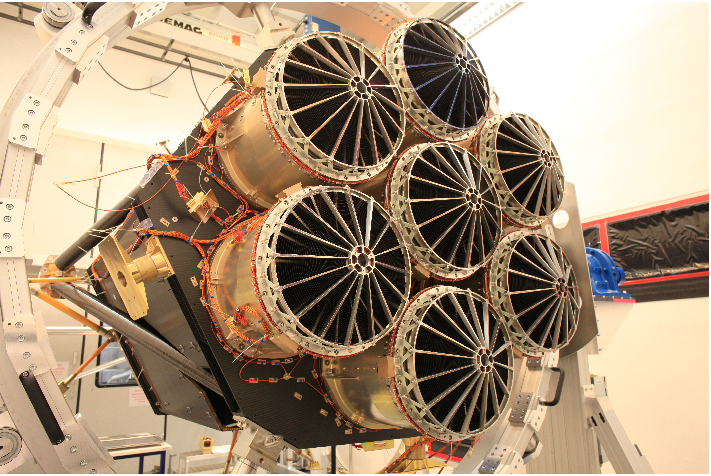

The observatory, called eROSITA, launched in 2019 and is the first space-based X-ray telescope capable of imaging the entire sky. It is the main instrument aboard the Russian-German Spectrum-Roentgen-Gamma mission, which sits in a region known as Lagrange point 2, one of five stable points around the sun-Earth system, where the gravitational forces of the two bodies are in balance. From this vantage point, eROSITA has a clear view of the universe, which it photographs with its powerful X-ray detecting instruments.

Last month, the team behind eROSITA, led by scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Germany, released the first batch of data acquired by the instrument to the wider scientific community for exploration.

Video: Milky Way’s core overflows with colorful threads in new X-ray panorama

Imaging the whole sky in X-rays for the first time

The telescope has already led to interesting discoveries, including that of giant X-ray bubbles emanating from the center of the Milky Way. With its first public science release, eROSITA is poised to shed light on some long-standing cosmological mysteries including the distribution of the elusive dark energy in the universe, the mission’s senior scientist Andrea Merloni told Space.com.

“For the first time, we have an X-ray telescope that can be used in very similar ways as the large field optical telescopes that we use today,” Merloni said. “With eROSITA, we cover the entire sky very efficiently and can study large-scale structures, such as the entire Milky Way.”

All-sky surveys, such as the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission or the ground-based Very Large Telescope of the European Southern Observatory, image vast areas of the sky at one sweep, allowing astronomers to understand the motions of entire populations of stars and other celestial objects. Gaia, for example, observes nearly two billions of stars in the Milky Way and measures their positions in the sky and distances from Earth with unprecedented accuracy.

“Large survey optical telescopes are now quite commonplace because they are very useful to study cosmology [the evolution of the universe] and things such as dark energy,” Merloni said. “But optical telescopes are much easier to design than X-ray telescopes.”

However, some of the most interesting objects in the Universe don’t emit light at visible wavelengths and remain therefore mostly hidden to optical telescopes. That includes black holes and neutron stars. But also distant galaxy clusters, the conglomerations of galaxies that represent the most complex structures in the Universe, are more easily observed in X-rays.

Previous X-rays telescopes, however, such as ESA’s XMM Newton, or NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, could only observe rather small sections of the sky in one go.

“The X-ray telescopes so far have been able to look very deep into the centre to observe the early Universe,” Merloni said. “But it has always been very difficult to compile large populations [of black holes, neutron stars and clusters] and create a large catalogue that you could then use to study their cosmological evolution.”

The eROSITA telescope reuses a lot of the technology originally developed for ESA’s veteran XMM Newton, which has been orbiting Earth since 1999. The technical adjustments made by the Max Planck Institute team and their collaborators enable the new telescope to produce images of the same quality as XMM-Newton but over a much larger field of view, Merloni said. SOURCE: Space.com.