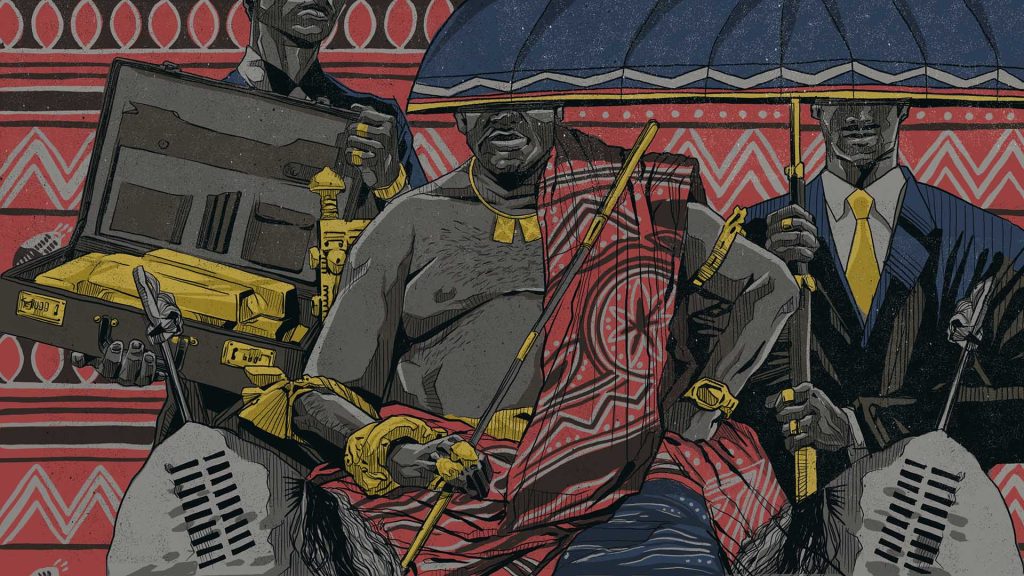

…How international gold dealers exploited a tiny African kingdom’s economic dream

By Micah Reddy and Warren Thompson – Above Image Credit: Sindiso Nyoni, ICIJ.

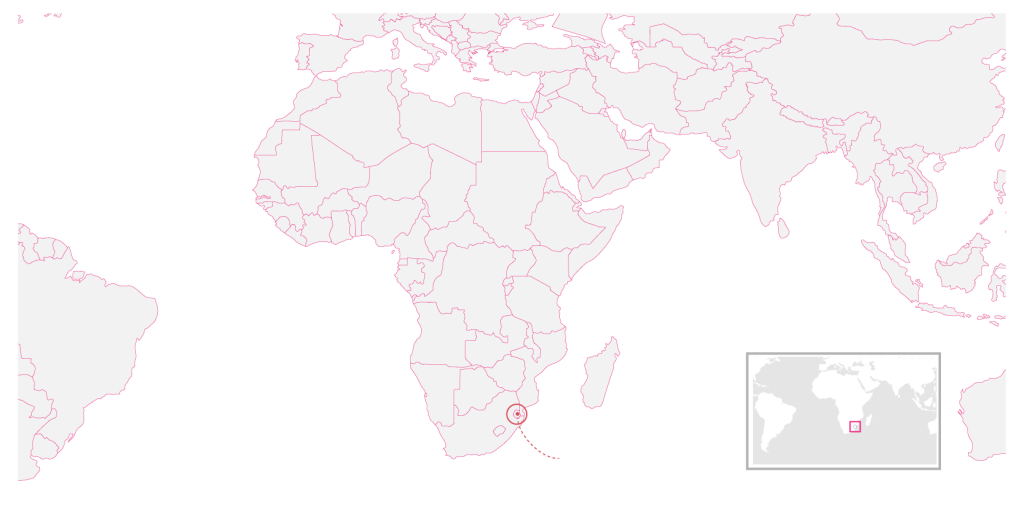

Against a backdrop of rolling hills and sugar cane fields, a generous stretch of cleared land borders the small industrial town of Matsapha in central Eswatini, a tiny landlocked African country between South Africa and Mozambique.

Musa Motsa, a 51-year-old farmworker and father of six, grew up on this land. He and his family used to grow cabbage and other crops here and collected water from a nearby spring. But in 2012, they were forcibly removed — along with around 180 other people — to make room for a government-sanctioned “special economic zone,” or SEZ, called the Royal Science and Technology Park.

The “brainchild” of Eswatini’s king, Mswati III, and his “insatiable desire to help stimulate economic growth,” as one press release put it, the SEZ was meant to be an oasis for new business. Instead, grass and weeds are slowly reclaiming vacant plots. Wide, empty boulevards go nowhere, lined with streetlights that aren’t in operation. One lone building — a multistory government office complex — stands in a surreal ghost land of nearly 400 acres.

There are no remnants of the vibrant community where Motsa once lived. And there’s nothing pointing to the businesses that, on paper at least, are based here: mysterious gold refineries channeling millions of dollars to Dubai.

Eswatini — formerly Swaziland until its king unilaterally changed the country’s name in 2018 — is Africa’s last absolute monarchy. A tiny kingdom of 1.2 million people, with an economy heavily dependent on its larger neighbors, it’s plagued by high unemployment: Nearly 60% of Swazis under age 25 are out of work. The country’s life expectancy in 2021 was 53 years for men and 61 for women — among the lowest in the world — driven by the world’s highest prevalence of HIV among adults (around 26% of the adult population is living with the virus).

While the majority of Eswatini’s population faces grinding poverty, King Mswati III and members of his expansive family — reportedly including 11 wives and over 30 children — have earned a reputation for conspicuous consumption. The king’s collection of bespoke watches alone is worth millions of dollars, and his fleet of luxury cars and jets belies the tattered state of an economy that is smaller than Fiji’s.

By offering favorable incentives like corporate tax exemptions, the SEZ would, in the words of the country’s officials, promote exports and growth, create jobs, and spur technological development. It was to be Eswatini’s fast track to “first-world status,” according to the press release.

To do this, the government enacted a series of forced evictions from mid-2012 until the end of 2014, according to Amnesty International. Only one of the evicted people was recognized by the government as having a right to live on the land and was compensated with an alternative home. All the others — like Motsa and his family — were, in the government’s view, “illegal squatters” on land that was held by the king “in trust” for the Swazi people. When the king allocated the land to the Ministry of Information and Communication Technology for what would become the SEZ, the residents were told they would have to leave.

Motsa now lives in a small home provided by his employer, about nine miles from where he grew up. Sitting in his living room, the king and queen mother watching from a calendar on the wall above, Motsa’s anger is discernible as he recounts the armed riot police’s eviction of his family a decade prior. “It was painful,” he told ICIJ. “We slept in the open — no roof over our heads.” He says people pleaded with those carrying out the demolitions to wait until they could remove their belongings, but some houses were destroyed along with their furnishings. He managed to salvage a few corrugated iron sheets that lie in a pile outside his new house. “It’s been a lifetime of pain,” he says.

Motsa was lucky enough to have somewhere else to go. Others were left homeless. Some took refuge at a nearby Lutheran church. “We were just treated like dogs and chased away,” says Ntfombiyenkosi Dlamini, who, she says, had lived within the boundaries of what is now the SEZ since the 1970s. When the evictions happened, her family had to move the graves of buried relatives. Then her family split up and are now scattered across the country.

Ostensibly, the SEZ is home to two gold refineries: Mint of Eswatini Pty. Ltd. and RME Bullion Pty. Ltd. Neither of these refineries existed, however. Mint of Eswatini was a shell through which millions of dollars in suspicious transactions flowed, and RME was suspected of being a link in an illicit gold trading operation. The companies eventually set off alarm bells at the Central Bank of Eswatini and the Swaziland Financial Intelligence Unit, now known as the Eswatini Financial Intelligence Unit, an independent statutory entity within the kingdom that aims to “provide financial intelligence that safeguards the local and international financial system” from money laundering, terrorism financing and other illicit activity.

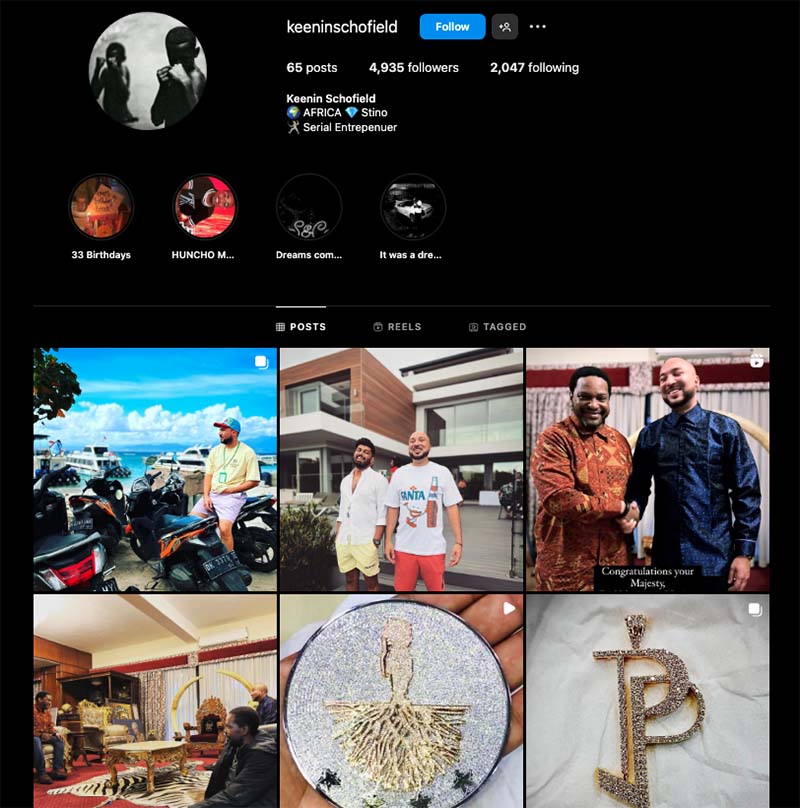

Leaked documents reveal that Eswatini’s authorities were concerned that the gold refining companies were exploiting the SEZ’s loopholes to evade taxes, illegally move money abroad, or potentially move illicit money through the kingdom. Rather than drawing in productive investment and spurring economic growth, the SEZ may have turned the country into a hub for money laundering, the central bank and EFIU feared. The activities of two figures close to the king concerned the EFIU: Swazi jeweler Keenin Schofield, one of King Mswati III’s sons-in-law, who was once found guilty of and fined for diamond smuggling, and Alistair Mathias, a secretive and politically connected Canadian businessman involved in gold trading and construction.

Over 890,000 leaked documents from the EFIU were obtained by Distributed Denial of Secrets, a nonprofit devoted to publishing and archiving leaks, and shared with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and seven media partners as part of the Swazi Secrets investigation.

The documents show that in less than one month, from late November 2018 to mid-December 2018, 10 transactions worth about $4.7 million at the time (more than 67 million South African rands) were made from a murky South African “cash-in-transit” company to Schofield, who then sent about the same amount to Mint of Eswatini in the SEZ, from where the money went on to Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Eswatini’s authorities deemed the transactions suspicious.

The EFIU’s analysis led it to suspect an illicit operation to launder money and smuggle gold through the kingdom — connecting Eswatini to a much larger operation involving gold smuggling and money laundering across southern Africa and stretching to the gold markets of Dubai. This operation was exposed by Al Jazeera’s Investigative Unit, a partner in Swazi Secrets, in its 2023 Gold Mafia investigation. Al Jazeera’s exposé showed how rival gangs controlled Zimbabwe’s gold trade, smuggling the precious metal across borders and helping Zimbabwe’s regime evade sanctions. These gangs, linked to heads of state and their inner circles, help criminals launder illicit money through international gold transactions.

Money movers

While the SEZ garnered little interest among international investors, Keenin Schofield and Alistair Mathias smelled opportunity.

Schofield, a jeweler who grew up in Swaziland and South Africa and is now in his mid-30s, sells high-end watches and custom-made jewelry to global elites and wealthy celebrities. (He was also once arrested for smuggling: In 2009, when he was 20, he was convicted by a Zimbabwean court of illegal possession of diamonds and fined $400.) His Instagram accounts feature professional footballers, rappers and royals flaunting six-figure gold watches, diamond-encrusted Schofield & Co. necklaces and other assorted bling.

Schofield’s links to the Swazi royal family are less visible. There is little public information on his marriage to Princess Temtsimba, one of the king’s daughters, but he confirmed the marriage to ICIJ and said he and the princess have two children.

Mathias, 40, told Al Jazeera he operates out of Dubai but works in Switzerland and several countries in Africa, where he claims to be close to political elites. He said to Al Jazeera’s undercover reporters that he has pumped money into electoral politics in Africa, including in Ghana.

His father moved from Canada to Dubai in the 1970s and worked in shipping, Mathias told Al Jazeera. He said he began his own career in banking and private equity before moving into the gold trade and construction.

In the documents, the EFIU notes Mathias’ involvement in a legal matter in which he “was accused by his business partner of defrauding him in a gold business.” A UAE court exonerated Mathias.

What’s not mentioned in the leaks is the allegedly central role Mathias played in the sprawling, gold-based money laundering operation exposed by Al Jazeera in 2023. Al Jazeera’s investigation implicated Mathias alongside his business partner, convicted Zimbabwean gold smuggler and former international rugby player Ewan Macmillan, nicknamed “Mr Gold.”

In its investigation, Al Jazeera uncovered rival gold smuggling and money laundering syndicates made up of many characters (“from new-age pastors to old-school smugglers, and from diplomats to the Zimbabwean president’s niece,” as one story notes) moving billions of dollars in illicit gold and laundered cash. Al Jazeera described Mathias as the “brains” behind one such operation — an “architect” of elaborate schemes to launder money “for people all over the world,” allegedly including African politicians.

Mathias told Al Jazeera’s undercover reporters that he “moves” gold worth between $70 million and $80 million each month through Ghana and southern Africa. Mathias, who travels frequently to Eswatini, also boasted on camera about being a friend of Mswati III. Schofield told ICIJ that a friend of his introduced him to Mathias in mid-2018. Soon after that, the two were in a business relationship.

The SEZ launched in the first half of 2018, offering favorable incentives: exemptions from corporate tax and foreign exchange controls, and the “unrestricted repatriation of profits.” By June, Mint of Eswatini was registered in the SEZ, with its two directors, Schofield and Mathias, each owning 50% of the shares.

On Nov. 2, 2018, a South African cash-in-transit company (one that securely handles and moves cash) called Asset Movement Financial Services sent $414,000 to the account of Schofield’s customized jewelry company at First National Bank in Eswatini. Later that day, the leaks show, Schofield & Co. sent the bulk of the cash on to Mathias Holdings in Dubai, in a payment labeled “Mathias.”

Dubai is among the “jurisdictions around the world which make money laundering incredibly easy, which are basically not compliant with anti-money laundering provisions and where it’s almost impossible to see those authorities collaborating in tracking illicit financial flows,” says Paul Holden, a money laundering expert and director of investigations at Shadow World Investigations, a nonprofit focused on exposing global corruption.

The Nov. 2 payment was part of a pattern of transactions — all originating from a company in South Africa, then routed via Eswatini (which is part of the Southern African Customs Union and whose currency, the lilangeni, is pegged to South Africa’s rand), and finally ending up in Dubai. Then the money began to flow via the newly formed Mint of Eswatini. In less than one month, 10 more transactions were made to Schofield’s account, totaling about $4.7 million at the time. The money was then sent in nine transactions to Mint of Eswatini, which sent it to Mathias in Dubai through three transactions.

According to a document from the leaks that compiled suspicious transactions, this “layering” pattern — a series of complex transactions that make the illicit source of the money difficult to track — raised suspicions, among Eswatini authorities, of money laundering.

In an interview, Schofield said he had wanted to establish a refinery before he met Mathias: “I had met all the relevant stakeholders in Eswatini to get the licensing done … but I just wasn’t able to get it over the line in terms of raising enough capital,” Schofield told ICIJ.

Schofield says that’s where Mathias came in: He would put up the money and was “leading” the project. Schofield, meanwhile, would act as the local partner, he says, by building relationships in Eswatini and introducing Mathias to “relevant people.” His own company, Schofield & Co., would be one of the “agents” that would buy finished gold products like gold coins from Mint of Eswatini and sell them on.

A royal mint

Asset Movement Financial Services was little known at the time but soon began to attract notoriety for its involvement in alleged money laundering. Around the time AMFS began to funnel money to Schofield & Co., South African media revealed its alleged role in the looting of a small Namibian bank, Small and Medium Enterprises Bank Ltd., or SME Bank. Liquidators for SME Bank, which collapsed amid massive fraud, alleged that a portion of the millions of dollars stolen from the bank was laundered through AMFS. The liquidators labeled AMFS a “money laundering machine” and successfully froze the company’s accounts. A report by the EFIU noted the bad publicity around AMFS.

From August 2018 to June 2022, a South African government commission investigated state capture — a type of political corruption in which private interests influence a government’s decisions to their own advantage. The commission’s legal team alleged that AMFS laundered money from a corrupt airline deal. In its final report, the commission found that AMFS did not simply transport money like a traditional cash-in-transit company but operated like a bank, receiving deposits from clients online and paying out those deposits in cash.

On Nov. 30, 2018, AMFS sent Schofield & Co. more than $629,000. The following Monday when banks opened, Schofield & Co. passed the identical amount on to Mint of Eswatini. That same day, Mint sent the amount, plus a little extra, to Mathias in Dubai.

“It’s never proof of anything, but I always think it’s a red flag when you have a company that receives and dissipates money immediately,” says Holden. “Most legitimate companies hold on to some of their assets for reserves, they pay office costs. … They have all these extraneous expenses that reflect on their account, and you can tell an operating business’s account pretty quickly.”

Seven days after Mint’s payment to Mathias, on Dec. 10, $1.9 million landed from AMFS into the account of Schofield & Co. in two payments. Schofield & Co. paid the exact same amount to Mint of Eswatini — ostensibly for the “Purchase Of Gold Coins,” according to the leaks; Mint then immediately paid the full amount to Mathias, with the description “50 50 Coins 50kg.” Four days later, on Friday, Dec. 14, AMFS sent $2.1 million to Schofield & Co. — broken up into seven payments of varying amounts in what Holden says may have been an attempt at “smurfing,” where a transaction is separated into smaller bits to avoid reporting requirements and avoid detection. Schofield & Co. sent the money on, again in several payments, to Mint of Eswatini the following Monday, which then sent the total amount, less $14,000, to Mathias the next day.

That payment to Mathias in Dubai was the final transaction detailed in the leaks. Days after the payment, the EFIU compiled a report addressed to an Eswatini anti-corruption body — the Anti-Corruption Commission — stating that the “manner in which all these transactions are conducted especially receipts of huge sums of money which were immediately disposed-off [sic] to one of the Directors company in Dubai” led the EFIU to “be suspicious.” The report adds: “The fact that the directors were also involved in fraud and diamond smuggling” has led to the conclusion that the company could be involved in some sort of criminality.”

But there are tight constraints on the EFIU’s ability to investigate suspected crimes. It only gathers financial information, while other authorities, like the police, are responsible for further investigation and prosecution.

The EFIU is tasked with obtaining data from banks and financial institutions, analyzing it, and providing the financial intelligence to local and international law enforcement. The information gathering does not necessarily constitute proof of wrongdoing. Rather, it reflects authorities’ concerns and suspicions — and points to potential wrongdoing.

According to Holden, institutions like the EFIU are often “established to perform a sense of legality and to give credibility to a jurisdiction.” There are “all sorts of pressures” compelling countries to establish such institutions, even in an absolute monarchy.

“At the most basic level if you’re not going to have a financial intelligence unit you are going to be gray-listed by FATF [the Financial Action Task Force, the global anti-money laundering watchdog],” says Holden. “And that has all sorts of knock-on effects in terms of … whether you can get investment into your location. … Lots of companies would do due diligence and say, ‘We’re not interested in going to that jurisdiction at all.’ The reputational risks are way too high.”

When the Central Bank of Eswatini and EFIU began probing the businessmen behind the money, they noted Schofield’s run-in with the authorities in Zimbabwe 10 years earlier but not his royal connection. Nor did they mention Mathias’ involvement alongside Macmillan, his Zimbabwean business partner, in the gold-based money laundering scheme.

Gold is cash. It’s better than any currency. As long as you’re in gold trading you can move money anywhere.

— Alistair Mathias, speaking with undercover Al Jazeera reporters

They did, however, notice that the transactions involving the Eswatini SEZ did not make commercial sense. The EFIU noted that it was unclear whether the large transactions they flagged were for gold bought by the Schofield-Mathias companies as claimed, and what — if any — legitimate role Mint of Eswatini could be playing. A Central Bank of Eswatini letter from September 2019 asked: “why doesn’t Schofield and Company Jewelers directly purchase the gold bars from Mathias Holding FZC?”

Mint of Eswatini added no markup to the transactions, according to the letter; it was merely a conduit for the money and supposed gold bars and coins. Its bank account was opened days before it started receiving payments from Schofield & Co. And after a brief flurry of activity when the money from Schofield & Co. began pouring in, its account went dormant. According to documents reviewed as part of the Swazi Secrets project, to the central bank, the Mint appeared to be a “shell company” that added little to no value in the transactions. Although it was ostensibly a smelter of precious metal and jewelry, it had no facilities. The EFIU noted in early 2020 that the proposed refinery had “still not been established” on the nearly 20 acres of SEZ land allocated to the company.

“See, the best thing with gold is, it’s cash,” Mathias told Al Jazeera’s undercover reporters in a recorded conversation. “Gold is cash. It’s better than any currency. As long as you’re in gold trading you can move money anywhere.”

At some point in 2019, Mint of Eswatini’s accounts at its South African banker, First National Bank, were frozen “due to insufficient KYC information,” according to a report attached to the 2019 Central Bank letter. Banks are legally obligated to obtain KYC, or Know Your Client, information to verify the identity of a client and ascertain the risks of a business relationship with them — a standard measure to prevent money laundering. Later in the year, First National Bank “de-risked” Mint of Eswatini and fully terminated their relationship.

For his part, Schofield alleges that Mathias alone controlled Mint of Eswatini’s bank accounts, even though Schofield was a shareholder and director of the company. In an interview with ICIJ, Schofield claims he assumed that the cash coming from AMFS was Mathias’ money, used to purchase inventory like gold and jewelry: “We were receiving it [the money] and the idea was that that was part of the investment,” he told ICIJ. After the “glorious day” when the first batch of gold arrived at the airport, he claims he never saw any other deliveries.

Mathias sent money to Schofield & Co., Schofield alleges, which then passed the money on to Mint of Eswatini based on invoices Mathias generated. His relationship with Mathias turned sour, he says, when Mathias cut him out of business meetings. “From that moment I started pulling back,” says Schofield. In January 2019 the two parted ways, according to Schofield, and the Mint of Eswatini refinery was never built.

That month, Mathias set up his RME Bullion company in the SEZ. According to its website, RME (short for Royal Mint of Eswatini) was “endorsed by His Majesty King Mswati III” and “aims to strengthen Eswatini’s economic and commercial ties with other global commodity and financial centers by becoming the go-to partner for entities engaged in the precious metal business.”

This time, Mathias turned to another major South African commercial bank, Nedbank, which Eswatini’s Central Bank described in the report attached to its 2019 letter as having “weak anti-money laundering and counter financing of terrorism controls and is under close monitoring.”

Nedbank did not answer questions about its involvement with RME, saying that it “is bound by client confidentiality and therefore does not disclose client matters.” The bank added: “Nedbank Eswatini is governed by strict and robust internal policies as well as statutory/regulatory guidelines.”

Alarm at the central bank

At midday on Wednesday, March 20, 2019, a handful of Nedbank officials gathered in a boardroom on the second floor of their offices in the Swazi capital Mbabane. It was a meeting of the bank’s Limited High Risk Client Committee to discuss RME Bullion’s application to open a corporate account for working capital and the import and export of minerals.

Officials noted that RME’s business — mining and minerals — made it “high risk by nature,” according to the leaks. One official, however, pointed out that “there was an existing company mining gold” in the kingdom and “it makes sense that RME Bullion will be refining processed precious metals and exporting to other countries.” That seemed to assuage any reservations that the committee had, with one member going further and requesting that the company’s risk profile be downgraded to “medium.” The committee, after brief deliberation, decided to open the account for RME, subject to ongoing monitoring and due diligence.

In May 2019, RME received government approval to operate in the SEZ. By then it had also, with the assistance of Nedbank, been given “blanket cover” from the Eswatini Central Bank. This designation exempted it from exchange controls for up to $40 million a month — meaning it could freely move that amount through the country each month with little to no oversight.

Later that year, RME applied for a waiver to move $45 million in cash from Dubai, through Eswatini, to Zimbabwe — more than its $40 million threshold. RME had to explain its business model to the central bank to be granted the waiver. In its application, RME detailed its role as a middleman in a complex arrangement involving gold buyers in Dubai: The buyers would advance hard cash to RME, which would be flown into Eswatini and stored at RME’s premises. The Dubai clients would place orders for gold against the advanced funds. RME would then “source gold from Zimbabwe or the rest of Africa,” fly to the source and purchase the gold using the advanced cash, and then bring the gold into Eswatini. RME had also claimed that it was constructing a smelter in the SEZ; it would then “test and melt” the gold before shipping it to Dubai for refining.

RME’s pitch to the central bank and explanation of its business model raised eyebrows among officials, according to the leaks. They were concerned that the transactions — which would be dealt with in cash and outside the formal banking system — would not add any value to Eswatini, which RME itself admitted. They wanted to know why Dubai would not deal directly with Zimbabwe, at least while construction of the smelter was underway. Mathias’ answer was classic marketing spiel: He told the central bank that RME would be “marketing Eswatini as the new and upcoming trade area.” The central bank also viewed the Schofield-Mathias companies as politically exposed — carrying a higher risk of bribery and corruption, which it viewed as another warning sign.

In considering RME’s case, the central bank was forced to confront the risks posed by the SEZ, which had been legally established only the year before with the passing of the Special Economic Zones Act. Mathias argued that he had been “invited” to invest in Eswatini, with the promise that his company would enjoy the very favorable concessions of the SEZ. (The documents do not note who “invited” him.) In theory, he would not even require the $40 million blanket cover, he told the Bank, because being in the SEZ automatically implied no exchange controls and precluded the need for “source documentation required by banks to wire payments.”

The central bank highlighted the risk the SEZ posed as a potential gaping hole in the country’s economy, through which millions in illicit funds might flow, and which could make the country a haven for “criminals that will abuse the financial system.”

The central bank officials’ fears about the SEZ were confirmed when Mathias claimed to the bank that the SEZ essentially operated “as a country on its own and therefore, laws applicable to local companies do not apply to the operations at SEZ.”

To the central bank, the SEZ was a fait accompli, and it highlighted the need to better understand the SEZ’s “impact on the economy.” The bank warned in its September 2019 letter that “Transactions carried out in the special economic zone may never be of economic value to the country.” Worse still, the bank warned that the SEZ was a gigantic loophole waiting to be exploited by criminals and money launderers, and that its continued existence could have negative consequences for the country’s credit rating.

After considering RME’s requested waiver and reviewing its business model, the central bank revoked the company’s blanket cover. The bank also recommended “an inspection at RME Bullion to ascertain the testing and melting facilities as well as any economic activity and governance procedures at RME Bullion.”

In a recorded conversation with Al Jazeera’s undercover reporters, Mathias underscored how useful refineries are to his money “moving” schemes. In the video, Mathias tells an undercover reporter that someone wanting to conceal cash could “pay through the refinery.” He then explains: “I’ll play with the paperwork. I’ll make it look like you gave me gold or something like that. I’m just keeping it on deposit. Then you tell me, ‘Sell the gold.’ I’ll sell the gold so you’ve got cash in your account. You can do everything on the computer.”

Authorities in Zimbabwe, where the U.S. has sanctioned the president, vice president and senior government officials for corruption and human rights abuses, have not accused Mathias of any wrongdoing based on the findings of the Al Jazeera documentary. The country’s Financial Intelligence Unit —part of the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe — froze the accounts of some of those featured in the Al Jazeera investigation, including Macmillan’s. Around two months later, Zimbabwe’s FIU unfroze them.

It is not clear whether the central bank inspection of RME Bullion ever happened. But if officials had visited the site, they would have discovered a reality far removed from the impression given by RME’s website of a smelter operating at full steam in the SEZ. They would have encountered instead a vast expanse of emptiness.

‘I can’t sit here and deny things’

The paper trail in the leak does not shed light on where investigations ended up, and the Central Bank of Eswatini and EFIU did not respond to ICIJ’s specific questions. Instead, they said in a joint statement emailed to ICIJ that “we cannot respond to questions on any information relating to confidential communications and operations other than to entities legally entitled to hold this information.”

Schofield says that he only got a call from the central bank asking if he was still a director of Mint of Eswatini. “I said no, and they just said thank you,” and that was the end of the conversation, he says.

Schofield acknowledged that the convoluted transactions could have been an illegal scheme, but he blamed Mathias, claiming Mathias was essentially paying himself via a complicated detour through Eswatini. “I can’t sit here and deny things,” Schofield told ICIJ. “… But at the time I was a 29-year-old. … Of course now that I’ve grown up and gone through things, this is part of my entrepreneurial journey.”

Mathias did not respond to ICIJ’s questions for this article. However, in response to Al Jazeera’s investigation, Mathias “denied that he designed mechanisms to launder money and said that he never laundered money or gold or traded illegal gold or offered to do such things.” He also told Al Jazeera that he “never had any working relationship with Ewan Macmillan” and denied owning “any refineries in Dubai whether in his own name or through proxies.”

Whether RME continued to receive and make payments — and is still a functioning part of Mathias’ global network — also remains uncertain. But the central bank did underscore the “large cash transactions, uneconomical transfer of funds to foreign jurisdictions and large or rapid movement of funds” — all hallmarks of money laundering operations.

The EFIU put it more bluntly, writing that RME and those connected to it “might be using the country as a conduit for smuggling illegally obtained Gold out of Africa through Eswatini to the United Arab Emirates.” It also “suspected abuse of SEZ exemptions, privileges and tax exemptions.”

In conversations with Al Jazeera’s undercover reporters, Mathias and Macmillan — his business partner in Zimbabwe — gave clues about the funds coursing through the Eswatini companies. Macmillan seemingly spoke about using Eswatini as a conduit: “There’s other ways, we can push it [the money or gold] into Swaziland. You know where Swaziland is? … We can move it any way you want. We can make a plan.”

The project that was supposed to catapult Eswatini into “first-world status,” spur technological development, create jobs and draw the country deeper into the global economy appears to have done more to integrate the kingdom with illicit international networks. Holden says that at first glance it looks as if Eswatini may be “acting as the local outpost of a global money laundering network.” In the view of the central bank, the Royal Science and Technology Park had the potential to be an open wound through which Eswatini’s fragile economy risked hemorrhaging millions of dollars.

For Musa Motsa, the lofty promises of development are jarring. Looking out over the land that he was kicked off more than a decade ago — where he grew up and eventually built four small houses that he rented out — Motsa wonders what it was all for.

“I am 51 years old, and I don’t have my home,” he says. “… and the sad part is there is nothing here.” (Source: International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, ICIJ).