IAN ANDERSON OF JETHRO TULL ON CLIMATE CHANGE…

BY JEFF PERLAH FOR NEWSWEEK, Published June 3, 2017.

Climate change is on a lot of people’s minds these days, especially after President Donald Trump said he would pull the U.S. out of the Paris climate agreement. Views of the situation are even coming from the world of progressive rock.

One who is weighing in is Ian Anderson, the frontman and flautist of Jethro Tull, and that’s not surprising, considering Tull over the years has recorded a bunch of songs relating to the environment and climate change, including “Jack‐in‐the‐Green,” “North Sea Oil,” “The Whaler’s Dues” and “Wond’ring Again.”

Related: John Lydon says rotten things about Donald Trump, Green Day

“My generation and my parents’ generation are those responsible for most of what great-grandchildren will be inheriting, and a lot of it is going to be pretty ugly,” Anderson tells Newsweek. “Those who are climate change deniers, like your president [Trump], are unfortunately in a position to continue to do a lot of bad.”

Anderson has passionate opinions not only about our planet’s climate but its animals, specifically domestic ones. About a year ago, he joined the fight to end cat declawing in New York state: “We humans have 10 finger nails. Pulling nails was (and still is) a popular form of torture. If a cat is four-paw declawed, that is 18 claws compared to 10 human nails—1.8 times the pain…. If you can afford a cat, you can afford a scratching post. Sprays and other humane scratching deterrents are also available.” He added: “Declawing? Don’t even think about it—don’t you dare.”

Lately, he’s also been doing good from a musical standpoint. Jethro Tull is currently on tour in the U.S. (here is a full tour itinerary). And earlier this year, Anderson released Jethro Tull – The String Quartets, which made its debut at No. 1 on Billboard‘s Classical Albums Chart in April. It’s a record on which Anderson and the Carducci Quartet reimagine quintessential Tull tunes like “Living in the Past,” “Locomotive Breath” and “Bungle in the Jungle.”

It’s songs like these that have earned Anderson lofty status in the prog kingdom. Four years ago, he was crowned “Prog God” by the U.K.’s Prog magazine, which made perfect sense considering Tull has created some of the holy grails of progressive rock, including Aqualung, Thick as a Brick and Songs From the Wood (its 40th anniversary three-CD, two-DVD deluxe edition is out now). Tull have been at it for five decades, first as a potent blues-rock unit (as their 1969 debut, This Was, revealed) with an intriguing signature element: Anderson’s flute work. (In progressive rock, there is perhaps no image more iconic than that of Anderson standing on one leg while playing his flute.)

The blues continued to inhabit many of Tull’s releases, but over time, Tull blended other genres, including classical, to create their dynamic progressive rock.

In an interview with Newsweek, Anderson discusses The String Quartets, his performances of “Jethro Tull: The Rock Opera” and the differences between “progressive rock” and “prog-rock.” And talks up a storm about climate change, salmon farming, eating meat and The Walking Dead.

Congratulations on The String Quartets topping the Billboard Classical Album charts in April. Were you expecting commercial success with the record?

I think you gotta put the term “commercial success” into the perspective of classical music. It generally isn’t the case that the things that even top the classical charts are selling more than a few thousand copies. So it’s not quite the success that would apply if you were No. 1 in the Billboard 200 album chart, which of course means you would be, even in these days, selling a lot of copies. But I think the dedicated fans are going out to buy the record, and that’s very nice, and I’m hoping that they will enjoy it.

What was a main challenge of making a work of string quartets yet still retaining the fundamental nature of Jethro Tull?

Well, it was a side project that I had in mind to do for a while, and last year, there was the opportunity between tours, or sitting in dressing rooms, or in hotel lobbies, to work on the idea with our keyboard player John O’Hara. And we came up with a number of songs, some of which were challenging to convert into the traditions of the string quartet, with a classical sense of arranging and writing, and some of which were kind of easier. We put that together and I found a string quartet who were based in, as luck would have it, not far away from where I live [in the U.K.]; which was a great alternative to having to travel, perhaps, to Prague, to work with the Skampa Quartet, who I’ve worked with in the past and who are very good. And we recorded in the crypt of Worcester Cathedral, and then in a tiny church out in the middle of the countryside of the U.K.—not because I was looking for the acoustic value of those buildings but really just for the spiritual [environment] and the gravitas that comes from working in that kind of an environment.

Jethro Tull frontman Ian Anderson recorded ‘The String Quartets’ with the Carducci Quartet.ANNE LEIGHTON MEDIA

What songs lend themselves particularly well to the quartet?

We can take two extremes, one that was a bit more radical in the sense that it was rewritten as a classical fugue [“Aquafugue”], and arranged by John O’Hara, who has a classical training as a graduate of the Royal College of Music, and he did what I could not do, which was to put it into an authentic fugue format. But as the piece progresses, you begin to recognize what it is you’re listening to, and the elements of the more familiar refrain become increasingly obvious. But there are other things that were perhaps a little less obvious, and maybe a little more playful, like taking the song “We Used to Know,” which is often talked about in comparison to the Eagles song “Hotel California,” which employs the same chord sequence, not really the same melody, and certainly very different lyrics. But I thought it would be rather fun to cast some elements of the music of my song, which preceded “Hotel California” by three or four years, to playfully make the comparison, and so I brought a little humor into the picture there, and I did a long track of a piece of serious music by J.S. Bach [“We Used to Bach (We Used to Know/Bach Prelude C Major]—the prelude in C major which is a Piano arpeggio piece—on which I crafted a melody of my own devicing.

The idea that “We Used to Know” influenced “Hotel California” has been written about before.

I’m sure if you google it you’ll find many people making the comparison. It’s not me making the comparison. It’s something that’s quite often talked about on the internet and elsewhere. I don’t think they copied. They were a band that first toured with us in 1972, so sometime after we had recorded “We Used to Know,” maybe we were playing it at that time. But the Eagles were at that point just beginning their career, and they were on tour with us as the opening act. They were a different kind of band—very kind of country rock. I don’t think our audience particularly liked them, and I don’t think the Eagles particularly liked us. But I don’t think they were guilty of plagiarism. It’s just, you hear something in the back if your head, it kind of sits in there along with a whole bunch of other stuff. You know, there’s only 12 notes in the musical scale, and just so many chords. I’m sure you’ll find that same chord progression having been used several times in the history of planet earth. I’m not accusing them of anything.

Ian Anderson performs ‘Jethro Tull: The Rock Opera’ at the Lowry Theater, in Salford, in Greater Manchester. NICK HARRISON

You worked with John when you toured “Jethro Tull: The Rock Opera,” a performance about the namesake of your band. Can you talk about the opera?

The songs in the rock opera, for the main part, are fairly well known Jethro Tull songs that are slightly adapted to tell the imaginary story of Jethro Tull, the agriculturalist, the inventor, but imagining him in the present day. And what might he be doing today if he was involved in a third agricultural revolution to try to work towards increased production in order to feed an ever-enlarging population and an ever-more-hungry population, as more and more people feel they gotta have their three meals a day of red meat and potatoes, and whatever else you guys eat such a lot of. It’s what was meant to be a look at the realities of modern agriculture and modern methodology and the stark reality that we are going to have to produce food in ways that many people will find difficult to cope with, whether it’s bio-engineering of the foodstuff we eat in the future or whether it’s even alternative sources of protein using grasshoppers or worms…. In many parts of the world people are starving; times are going to be hard in years to come as climate change kicks in and the effects of very erratic weather will definitely take their toll on many traditional grain-producing areas of the world, the U.S.A. being one of them.

Scottish musician and singer Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull smoking a pipe, circa 1975.EXPRESS NEWSPAPERS/GETTY

Over the years, Jethro Tull has explored issues relating to the environment, including climate change.

My interest in climate change goes back to about 1974. There was a track released on the War Child album called “Skating Away on the Thin Ice of a New Day,” which was a piece talking about climate change. Albeit in the 1970s, it was thought that we were possibly heading towards another age of global cooling—a mini ice age. In fact, scientists then had got it wrong because when the ice core samples started to kick in in the ’80s, and the reality began to emerge, of gradual incremental change, then global heating became the likely prediction, and of course that, for the last 10, 15 years, has been the agreed likely future of the planet aggravated in part, I’m sure, with what we would call natural change in climate but certainly by the effects of human activity. If it wasn’t for the fact that many Chinese cities have absolutely been deviled by smog and terrible atmospheric conditions, I doubt the Chinese would be doing what they’re beginning to do now, which is to, in some cases, lead the charge towards more environmentally conscious ways of producing energy. But I’m afraid the trend is in the opposite direction in your country right now. It should be scaring the proverbial out of you.

It is.

And in other ways it isn’t because you always find ways to unfortunately excuse the dependency that you have on fossil fuels. And the dependency you have on personal transport, for example. And the dependency that you have or you think you have on eating vast amounts of meat, which is very expensive to produce, very energy intensive, very damaging to the environment. In South America and North America, there is a culture of eating really, really a lot of meat. I’m not a vegetarian, I mean I eat meat, I should be having some meat tonight in a pie. But I don’t eat meat every day. I enjoy it when I eat it but I’m very conscious of placing some restriction on the amount that I eat. And I choose not to drive a car. I choose not to be dependent on transport, which is very inefficient in terms of its impact on the environment and its costs. I use public transport. I travel in the back of the airplane; on short and medium journeys I travel in the train. I should be on the train tomorrow traveling into London. I use the underground, the tube, the subway system, or a bus, or I walk. But I’ve never been interested in owning a motorcar. Being a passenger in a car, and gas-guzzling my way 200 miles to go to London and back—I think it a little inefficient.

A promotional portrait of Scottish musician and singer Ian Anderson of the group Jethro Tull singing into a microphone onstage.HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY

What happens when you have to get somewhere in a pinch and you can’t get there by bike, walking or public transport?

I change my plans usually. Like everybody else, I think the answer you’re looking for is, “I get out my smartphone and I ask Mr. Uber to to send me a car.” But these “What do you do when?” circumstances are exceptions. When you have the choice, when you can make the choice about traveling more economically, and more consciously, then I use public transport out of preference. I know there’s a lot of people who can’t do that because there isn’t any public transport. Of course that does apply in much of America, where it is a car-based society; there aren’t too many options. You have Greyhound buses but not much of a train network compared to Europe and other countries. You can argue that you don’t really have those options, but it’s time they were there.

In April, you traveled to Australia to perform, and made the trip by plane.

Being in the company of 300 other passengers, on a very large airplane, is the most economic way to do that. If I were to do that in private jet, then I think you could accuse me of the same hypocrisy as we might apply to certain other people who do that. On the one hand, to espouse concerns about the environment and then on the other hand jump into their private jet to go to the next climate change conference—plenty of hypocrites like that around.

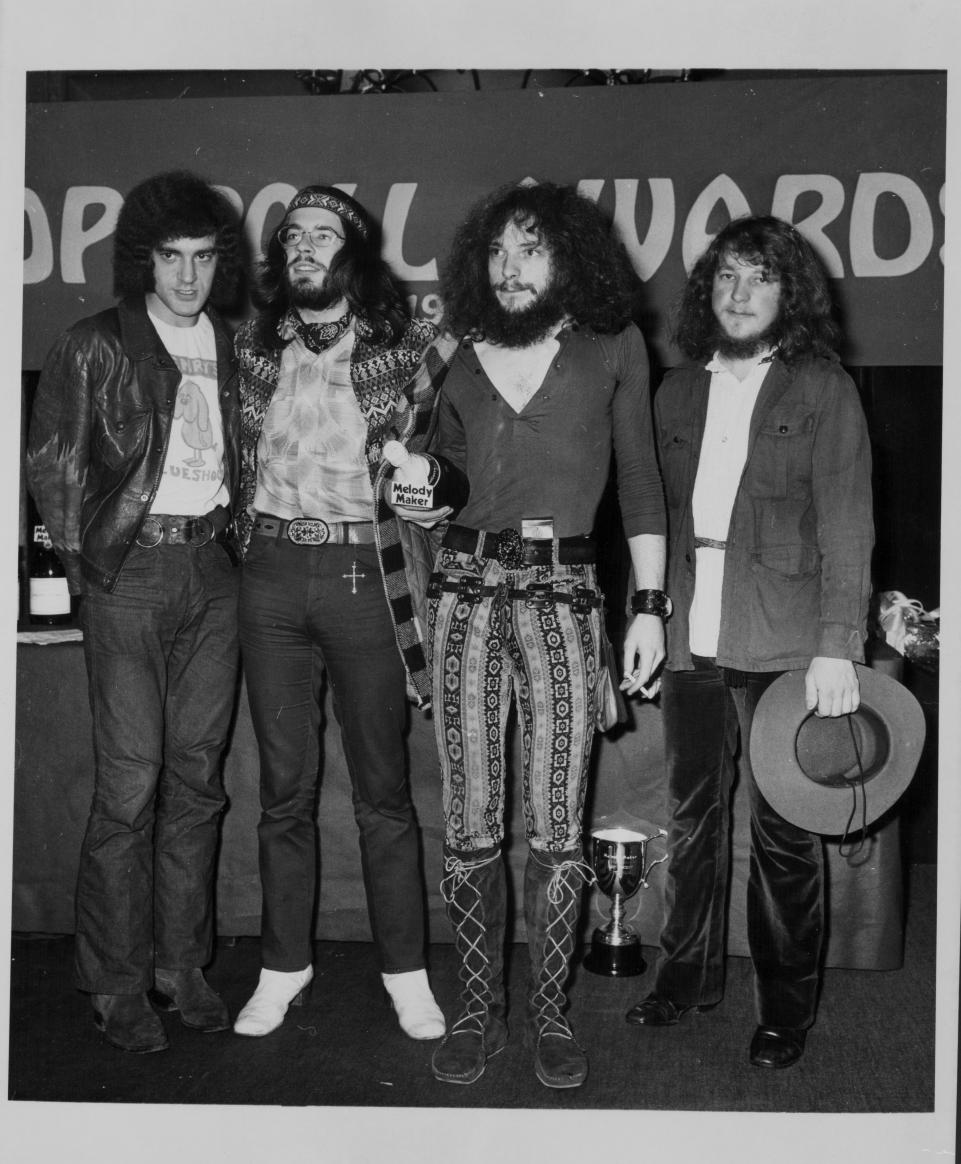

Jethro Tull holding their award for ‘best group’ at the Melody Maker Pop Poll Awards, Waldorf Hotel, in London, on September 17, 1969.TED WEST/CENTRAL PRESS/GETTY

Let’s return to the topic of ecology. A while back, you were involved with salmon farming.

I became interested in agriculture as a child because I lived on the edge of a city, and I was kind of interested in farming generally. So when agriculture became in a position to develop in a more scientific and technological way in the ’70s, I became interested in that. It was something I entered into not just to produce salmon but other fish and shellfish too, because of an awareness that we were having to move forward in time and look to alternative and new developments in terms of food production. But of course, with anything like that, there are positives and negatives. And I finally got out of salmon production after 20 years because I felt increasingly uneasy about some of the practices involved and the industrialization that had taken place, where instead of being lots of small farms in the hands of small companies, or individuals, it was essentially a very few big corporations running the whole show. And I was concerned about the sourcing of feedstuff. I decided I wasn’t in a position to go on defending the industry as I had, and decided it would be better to move on.

It doesn’t mean that I don’t eat farm salmon. I occasionally do eat farm salmon. But I think there is some reason to consider being careful with your diet in regard to sourcing [with] almost everything we eat. And fish and wild fish and farm fish, you really do have to pay attention to what are the production methods. There are some fish, for instance, that I would strongly advise you not to eat at all, or once a year if you’re being a bit racy. That’s not my business to tell you that. I can, because I read a lot of information that does become available from research institutes and scientific bodies. Even though I’m not commercially involved in it anymore, I’m interested in the topic, and I’m interested in my own health and in the health of people around me, so I think I have a pretty good idea where I want to buy my fish from [laughs], and where it has been caught. You can’t be too pussyfooting around. We’ve all got to eat, but I think you do have to make educated choices, and not just consume something just because you like it and you think all the stories are “scare stories.” Some of them indeed are, but some of them do have some element of truth about them, so I think we’ve all got to be responsible and do our little bit of research, especially when we’re feeding a family, our children or our grandchildren.

Can you talk more about the salmon farming business you owned?

I was employing about 400 people on our salmon farms and in our three processing plants, and we were one of the bigger companies in the U.K. producing fish for the major multiple chains and a few specialty shops. We were kind of a medium-sized company, in what began as a relatively small field of endeavor. But farm salmon these days is very big business, and as it became bigger business, I decided it was time to move on.

Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull performs at the Lowry Theatre, in Salford, Greater Manchester.NICK HARRISON

In 2013, you received the Prog God Award at the Prog Magazine Awards in London. It was presented to you by Rick Wakeman, who received the honor a year earlier. What are your thoughts on the meaning of prog-rock?

Well, I think progressive rock was a term that I first read in 1969, and it was a term being applied to, amongst others, to Jethro Tull, and I thought that was a pretty good description. I rather liked the idea of progressive rock music. It sounded forward-thinking, moving, not just taking something that was an established genre but something that was continuing to develop. I rather liked that term, but within a couple of years, progressive rock had been shortened to prog-rock and was often used in a disparaging way to describe bands such as Emerson, Lake and Palmer or Yes or early Genesis. And there was perhaps a degree of showiness, a degree of self-absorption, in the work of some of those bands, and in comparison, Jethro Tull was usually a little bit more rough-edged, and not quite as demonstratively showy as perhaps Emerson, Lake and Palmer were. But that doesn’t mean that I couldn’t do something that fitted the “prog-rock” genre, which I did, with the album Thick as a Brick in 1972, very deliberately to kind of spoof it, to make a little bit of a send-up of the genre. But in doing it, of course, I had to write something on a grand scale, but it was a little bit tongue-in-cheek. This was the era of Monty Python, this was the era of there being a rather surreal form of British humor, which was expanding across the planet courtesy of Monty Python, although there were other British humorists who had quirky, rather surreal way of presenting things.

After creating Thick as a Brick, Jethro Tull continued to be progressive in many ways, including on Songs From the Wood, which blended rock with British folk music and other forms.

Yes, I think that that really is the main identifying feature of the Jethro Tull repertoire over the years. As it does evolve, it continues to progress, but at the same time, I don’t usually leave my early roots completely behind. I think there’s always a good source of musical approach in things that I’ve done in the past, so I often go back to take elements, ideas, from things that I’ve done before, and bring those into play alongside new ideas and things I have not done. So I try and balance up that general picture.

How did the making of Thick as a Brick go?

The music was written actually very quickly. I would be writing five minutes’ worth of music in the morning, taking it to the guys to learn in the afternoon, and to rehearse…. And then we went into the studio and recorded it in a period of, I think, probably less than two weeks, so it was done quite spontaneously. But the other guys in the band [hadn’t] got a clue where it was all heading [laughs]. They probably didn’t hear the songs sung or the lyrics until the album was actually released.

How did that differ from Songs From the Wood?

Songs From the Wood was an album where some of the band members were much more involved in the arrangements, and being creatively involved in the studio. So they’re all different, in their different ways. And there is an element of something I suppose you would call progressive rock about many of our records, perhaps even you might use that term to describe most of them. But prog, no. I think when we’re talking prog-rock, as such, we’re really just talking Thick as a Brick, maybe A Passion Play, but that’s about it.

Ian Anderson, the leader of the British rock band Jethro Tull, performs during the Festival du Bout du Monde, in Crozon, western France, in August 2007.FRED TANNEAU/AFP/GETTY

In 2012, you released Thick as a Brick 2. How did that record catch us up with the original album’s protagonist, Gerald Bostock?

Thick as a Brick 2 was written in the end of 2011, but recorded in 2012, and it was a “what if” kind of imaginate of what might have become of [central character] Gerald Bostock, by making a list of possible outcomes to his life as an adult. And I decided that rather than pick any one of them, that I would explore of a number of alternative scenarios.

The point being all of us face in our lives certain potential forks in the road where we can go this way, or we can go that way. And perhaps it seems rather random, [but] maybe on the other hand it’s almost [a] preordained future that we have facing us as young men and women. I just explored some of those ideas in a way which was sometimes sort of upbeat and playful, sometimes a bit foreboding and worrying. But what faces every young adult is the crossroads, which way to turn. And sometimes we feel pushed to one direction or another, but I thought that was a useful voyage of discovery in the musical sense.

Another classic Jethro Tull album, Aqualung, voiced a number of socio-political messages—about the hypocrisy of Christianity in England, for instance.

Well, you know, I’m not a person who always writes music that has to do with some social consciousness, that’s putting forward some social message or criticism or political stance. But from time to time I write music which is, perhaps, headed in that direction. And sometimes it’s more whimsical, observational songs that are a little more light-hearted. And Aqualung is an album that contained both. It had two or three songs that were kind of about difficult topics, about organized religion, about homelessness, prostitution, whatever it might be. But also there were whimsical, fun, upbeat songs that I felt quite deliberately should be there in order to balance the album up so there wasn’t just too much of the same thing. And I think we were fairly successful in doing that.

Let’s jump to a far different topic, The Walking Dead, which stars your son-in-law, Andrew Lincoln. Are you a fan of the show?

Well, it would be wrong to call me a fan of the show. I do watch it from time to time. But I’ve long missed so many episodes that I really don’t know what’s going on anymore, and all the actors inevitably change as they get eaten by zombies and the core number of people who are surviving from the very beginning are now down to [a few] people. And of course we talk about it a lot because it’s very much part of his life, and something that I suppose over the years has rather defined him as an actor. But I think he would welcome the chance to do something very different from the character in The Walking Dead.

What kind of music are you listening to these days?

I tend to listen to stuff that gets sent to me, when people are asking me to play on their record, and I really do have to listen. I mean, I’ve got a couple of things sitting on my desktop on my computer at the moment. I’ve said, “Oh sure, I’ll play on your record, send it to me when you’ve got something for me to listen to.” Sometimes it’s people that you know, people who are long-established writers and performers, and sometimes it’s people that you don’t know who are just beginning their career or not particularly well known to the public. I play on things because I want to do it, not because I’m getting paid, because I’m not.

I never ask for money, because I think once you do that, you’re in danger of becoming a hooker. I do it out of the enjoyment of the music, or because sometimes it’s people who are friends and I feel obliged to do it, even if I’m maybe not wild about the music, but I manage to pluck the enthusiasm for two or three hours to do the job. Which is also a bit like a hooker, isn’t it, really?

But the difference is that I’m an unpaid hooker. But when I’m faking orgasm, pretending to enjoy what I’m playing, then at least I’m not getting paid for it.

In the last few years, the worlds of progressive rock and classic rock have lost some important musicians, including Chris Squire, Keith Emerson and Greg Lake. You’ve performed with some of these artists.

Yeah, there’s a lot of people I’ve played with who are sadly no longer with us. I suppose it was a great privilege to have been able to play “Smoke on the Water” with [Deep Purple keyboardist] Jon Lord. It’s been a privilege to have had Greg Lake be my special guest on a couple of shows in Medieval cathedrals: in Canterbury Cathedral and Salzburg Cathedral; and to [play with] many other people who I’ve known over the years, and sometimes from different areas of life. Jack Bruce is someone who I didn’t know really in the early days of Cream, but I got to know him in later life and I’ve performed with Jack two or three times on TV shows. So yeah, there’s a few folks like that, and one day, I will be joining that elite group of people who aren’t there anymore, and someone will say, “Ah yeah, I remember playing with Ian Anderson, awfully nice chap.”

You also performed with Scott McKenzie during a 2004 concert.

I always said I would be terrified to do it. He asked me to play flute on “If you’re going to San Francisco” [sings], and it was one of the songs [“San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)”] I really, really don’t like. He was a very nice man. What could I do? I had to quickly learn the piece, and perform it with him. And if I hadn’t done my best, it would have been letting him down, it would have been letting me down, so I did what I had to do.