By TZ Business News Staff and Agencies.

Africa is grieving. Former president of Cuba Fidel Castro has died at the age of 90, his brother Cuban President Raul Castro announced late on Friday, November 25, 2016, according to the American news agency, Associated Press.

The news has been received with shock on the African continent where Castro played a deciding role in the struggle against colonialism, racism and other forms of oppression.

Reporting from Cape Town, News24 quotes the South African Government as grieving with the people of Cuba. Fidel Castro identified with and helped South Africa in the struggle against apartheid, President Jacob Zuma said in a message of condolences sent on Saturday after news of the Cuban liberation hero’s death.

Zuma said Castro, who died aged 90 on Friday, led the Cuban revolution and dedicated his entire life not only to Cuban freedom and sovereignty, but also the freedom of other oppressed people around the world.

”He inspired the Cuban people to join us in our own struggle against apartheid. The Cuban people, under the leadership and command of President Castro, joined us in our struggle against apartheid,” Zuma said. The two countries formed a strong bond of friendship after South Africa’s own liberation in 1994.

“As a way of paying homage to the memory of President Castro, the strong bonds of solidarity, cooperation and friendship that exist between South Africa and Cuba must be maintained and nurtured,” The South African President said.

Earlier, International Relations spokesperson Clayson Monyela said Zuma had called Castro’s brother Raul after the ”devastating” news to personally offer South Africa’s condolences.”We are standing with the people of Cuba at this difficult time,” said Monyela.

Fidel Castro’s anti-colonialist legacy

The Cuban leader was an energetic sponsor of socialist movements throughout Latin America and Africa. Castro helped many other people to obtain freedom–contributions he offered after winning his own freedom battles, according to Dr Manuel Barcia, the Deputy Director at the Institute for Colonial and Postcolonial Studies at the University of Leeds.

Soon after his capture in 1953 following an attack he led on the Moncada Army barracks, a young Fidel Castro was put on trial. While conducting his own defence, Castro accused Cuban President Fulgencio Batista’s regime of depriving Cuba of democratic rule and of establishing a dictatorship.

He finished his speech with a phrase that has become well-known in Cuba and abroad: “You can condemn me but it doesn’t matter: History will acquit me.”

Interesting enough, Castro’s subsequent actions have placed him in one of those inconclusive historical wormholes where agreeing on anything about him, let alone an acquittal for his actions, is almost an impossibility.

To some, he is an irredeemable monster who submerged Cuba into a long, dark age of tyranny and human rights violations. To others,

Soon after his capture in 1953 following an attack he led on the Moncada Army barracks, a young Fidel Castro was put on trial. While conducting his own defence, Castro accused then president Fulgencio Batista’s regime of depriving Cuba of democratic rule and of establishing a dictatorship.

He finished his speech with a phrase that has become well-known in Cuba and abroad: “You can condemn me but it doesn’t matter: History will acquit me.”

Interesting enough, Castro’s subsequent actions placed him in one of those inconclusive historical wormholes where agreeing on anything about him, let alone an acquittal for his actions, is almost an impossibility.

To some, he was an irredeemable monster who submerged Cuba into a long, dark age of tyranny and human rights violations. To others, he was a socialist superman who brought about social equality – at least partially for women and for Afro-Cubans – and who introduced free education and universal healthcare.

From an economic and political point of view, Castro’s rule was characterised by a catalogue of mistakes that over the years led to more than one “rectification of errors” campaign. Domestically, many of his policies seemed bound to failure from the start.

A heavy dependence on the Soviet Union as a result of an unremitting American embargo left the country exposed to the rough forces of the free market in the early 1990s, fostering an economic crisis known in Cuba as the “special period in time of peace” that arguably still continues.

Internationally, Castro’s involvement in world affairs, especially those concerning Latin America, was a thorn in the side of US policies.

His alliance with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, which brought the USSR and US to the brink of nuclear war in 1962, was an early red flag that Castro was not about to back off when it came to confronting US imperialism.

Castro lent his support to Latin American guerrillas fighting US-backed dictatorships countless times in the following decades, and in some cases supported movements taking on democratically elected governments, such as that of Romulo Betancourt in Venezuela in the 1960s.

Cuban secret agents wandered across the continent, training guerrilla commandos from Guatemala to Argentina. One of the icons of the Cuban Revolution, Ernesto “Che” Guevara, even lost his life while trying to set up a guerrilla movement in Bolivia to topple the government of President Rene Barrientos.

Beyond the confines of Latin America, Castro’s influence grew steadily throughout the Cold War years. In 1979, Cuba was elected to take over the presidency of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), an organisation formed in 1960 to offer a peaceful alternative to the belligerent East-West blocs that characterised the Cold War. Castro’s presidency of the NAM came as recognition of Cuba’s role in the international arena and was widely accepted and praised by all NAM members.

However, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan only three months into Castro’s presidency of the NAM caused havoc among the member states, and in particular affected Castro’s leadership since he was forced to side with the USSR.

In doing so, he failed on two fronts. He failed to stick to the actual principle of non-alignment enshrined in the NAM name and constitution, and he did so by turning his back on one of the NAM member states while supporting a Cold War power. Even though Castro’s stock took a massive tumble afterwards, he continued to influence international politics, and nowhere more so than in Africa.

Cuba in Africa

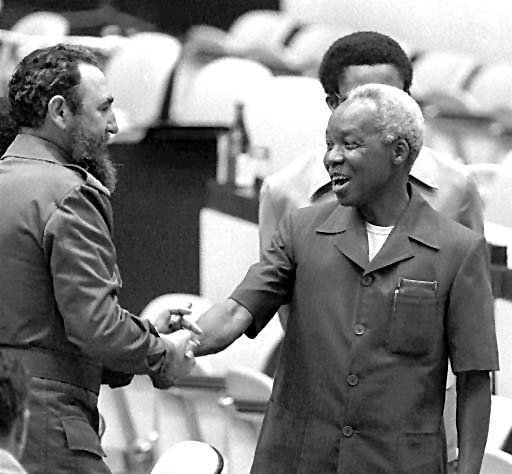

Fidel Castro meets Former Tanzania President the Late Mwalimu Julius Kambarage Nyerere, Chairman of the African Frontline States spearheading the struggle against apartheid and colonial rule in Southern Africa at the time.

Castro’s [and Guevara’s] role in assisting the decolonisation process in Africa was second to none. From the early 1960s, Castro threw all his support behind the Algerian liberation struggle against France.

Cuban doctors and soldiers were some of the first to arrive in Algeria to offer a hand to the independence forces fighting to push French colonialism out of their country.

In the following years, that support increased in size and scope across the continent. Castro offered Cuban support to the liberation struggles in Mozambique, Namibia, Zaire [now the Democratic Republic of Congo], Guinea-Bissau, and Angola, among many others.

In some cases, this support involved military interventions that did not always go according to plan. For example, in the mid-1970s after Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie was deposed by the Derg regime, Castro was forced to change sides – as the Soviets, East Germans, Czechs, and Americans also did – during a realignment of forces in the region provoked by ongoing disputes between Somalia, Ethiopia and Eritrea.

Cuban personnel were required to abandon their former ally Mohammed Siad Barre, the Somali president, who now sided with the Americans, and take sides with their new ally Mengistu Haile Mariam.

Cuban troops fought the Somalian invasion of the Ogaden alongside Ethiopian forces, and by remaining in Ethiopia gave at least tacit support to Ethiopian campaigns against Eritrean guerrillas fighting for independence.

This position almost certainly became a political dilemma for Castro, who until then had always supported anti-colonial movements of liberation across the world.

While Castro’s intervention in the Horn of Africa was characterised by dubious decisions and tainted by the purges that Mengistu’s regime would eventually carry out between 1977 and 1978, his involvement in the Angolan war is the outstanding episode in his career as a champion of decolonisation.

Not only did he demonstrate to the world that Cuba was far from being a pet project of the USSR – Cuba’s support for the socialist MPLA was done without the approval of the Kremlin and almost certainly against its wishes. It also helped raise his profile, and that of Cuba, to new levels of recognition and influence throughout the developing world.

Securing Angola’s independence: Cuban backing for the MPLA helped Angola to secure independence from Portugal in 1975, and helped repel the joint attempts of the South African apartheid government and Zaire’s Mobutu regime to occupy Angola.

Growing up in Cuba at the time, I can certainly say that I don’t recall any other Castro enterprise that united Cubans behind the regime to such an extent – except perhaps Cuba’s resistance to the 1983 US invasion of Grenada.

Contrary to what has been argued for years, Cuba’s involvement in Angola was a response to previous US and South African interventionism and to the very tangible threat of a South African invasion.

After almost two decades of struggle, when Cuba’s troops left Angola, they had secured not only the independence of the country, but had also contributed significantly to the independence of Namibia and to the fall of the apartheid regime.

Little wonder, then, that Raul Castro, in place of his brother, was one of the few world dignitaries asked to speak at Nelson Mandela’s funeral a few months ago.

Ultimately, Castro’s legacy in Africa is more of a Cuban legacy. Everywhere I have visited in Africa, from Dakar to Addis Ababa, from Niamey to Luanda, I have been welcomed with open arms and big smiles as a Cuban.

Former Zambian president Kenneth Kaunda, in response to a New York Times question about Cuba’s role in Africa, said: “I am not sure that there is a single Cuban in the African continent who has not been invited by some members of the continent. So long as this is the case, it is not easy to condemn their presence.”

“I am far from certain that history will acquit Fidel Castro. More likely history will record his journey through the past six or seven decades as controversial,” Dr. Barcia says.”Almost certainly, he will continue to be an irredeemable monster to some – and a socialist superman to others.”

Castro and the road to power according the American Television Channel CNN: It was a bearded 32-year-old Castro and a small band of rough-looking revolutionaries who overthrew an unpopular dictator in 1959 and rode their jeeps and tanks into Havana, the nation’s capital. The primary leader of the Cuban Revolution, Castro’s influence was to last decades.

They were met by thousands upon thousands of Cubans fed up with the brutal dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista and who believed in Castro’s promise of democracy and an end to repression.

That promise would soon be betrayed, though, and Castro held on to power for 47 years, until an intestinal illness that required several surgeries forced him to temporarily relinquish his duties to younger brother Raul in July 2006. Castro resigned as president in February 2008 and Raul took over permanently.

One Castro or another has ruled Cuba over a period that spans seven decades and 11 U.S. presidents. Fidel Castro outlived six of those presidents including Cold War warriors John F. Kennedy, Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan.

At the height of the Cold War, Castro used a blend of charisma and repression to install the first and only Communist government in the Western Hemisphere, less than 100 miles from the United States.

Cuba and the Soviet Union established diplomatic relations on May 8, 1960, further eroding the relationship with the United States. Castro, who had long blamed many of Cuba’s ills on American influence and resented the U.S. role in hemispheric politics, quickly intensified cooperation with the Soviet Union, which began sending large subsidies.

“Fidel Castro came to power with a conviction that he was going to have a major revolution in Cuba, that he was going to stay in power indefinitely, that he was going to fight American imperialism and that he needed a ‘daddy’ and his ‘daddy’ was the Soviet Union,” said Jaime Suchlicki, the director of the Institute for Cuban and Cuban-American Studies at the University of Miami.

‘Taunted, antagonized and irritated’

In doing so, Castro defied a hostile U.S. policy that sought to topple him with a punishing trade embargo that started in 1962 and continued for the rest of his life.

“He taunted, antagonized and irritated the United States for more than a half-century,” said Dan Erikson, a senior adviser for Western Hemisphere affairs at the U.S. State Department and author of “The Cuba Wars: Fidel Castro, the United States and the Next Revolution.”

Castro also survived numerous assassination attempts by the Central Intelligence Agency and anti-Castro exiles in the early 1960s. He took delight in pointing out how none of them succeeded, not even the plot that called for explosives to be placed in the ubiquitous cigars he later would quit smoking for health reasons.

Fidel Castro announces general mobilization after the announcement of Cuba blockade by US President John F Kennedy, in Havana, on October 29, 1962. “I have never been afraid of death,” Castro said in 2002. “I have never been concerned about death.”

Until his last breath, Castro held tightly to his belief in a socialist economic model and one-party Communist rule, even after the Soviet Union disintegrated and most of the rest of the world concluded state socialism was a bankrupt idea whose time had passed.

“The most vulnerable part of his persona as a politician is precisely his continued defense of a totalitarian model that is the main cause of the hardships, the misery and the unhappiness of the Cuban people,” said Elizardo Sanchez, a human rights advocate and critic of the Castro regime.

But Castro’s defenders in Cuba point to what they see as social progress, including racial integration, universal education and health care. Instead of blaming an inept socialist system, they fault the U.S. embargo for the country’s economic woes.

“What Fidel achieved in the social order of this country has not been achieved by any poor nation, and even by many rich countries, despite being submitted to enormous pressures,” said Jose Ramon Fernandez, a former Cuban vice president.

Castro’s political staying power was a source of puzzling consternation and bitter frustration for Cuban exiles, who never imagined he would rule so long.

“We came here with a round-trip ticket … because we thought the revolution was going to last days,” said Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, who came to Florida as a child and went on to become the first Cuban-American elected to Congress. “And the days turned into weeks, and the weeks to months, and the months to years.”

Castro occasionally allowed disenchanted Cubans to leave, with most going to the United States. More than 260,000 Cubans left in a U.S.-organized airlift between 1965 and 1973. In 1980, Castro let another 125,000 leave in the chaotic Mariel Boatlift. Among them were criminals released from Cuban jails who brought a violent crime wave to Florida.

At other times, desperate Cubans fled the island nation in makeshift boats across the treacherous Straits of Florida. Thousands died from drowning or exposure to the brutal Caribbean sun.

The center of the exile community is Miami, where the Cuban American National Foundation became a powerful lobbying group courted by U.S. politicians. For nearly five decades, pressure and political donations from the exile community have thwarted any efforts to lift the embargo.

Fidel’s early years: Castro was born August 13, 1926, in Oriente province in eastern Cuba. His father, Angel, was a wealthy landowner originally from Spain. His mother, Lina, had been a maid to Angel’s first wife.

Educated in private Jesuit schools, Castro went on to earn a law degree from the University of Havana in 1950 and became a practicing attorney, offering free legal services to the poor.

In 1952, at the age of 25, he ran for the Cuban congress. But just before the election, the government was overthrown by Batista, who established the dictatorship that put Castro on the road to revolution.

On July 26, 1953, Castro led a group of about 150 rebels who attacked the Moncada military barracks in Santiago in an unsuccessful attempt to overthrow Batista. Most of the attackers were killed. Castro and a handful of others were captured. The attack made him famous throughout Cuba, but it also earned him a 15-year prison sentence.

At his sentencing, Castro told the court, “Condemn me, it doesn’t matter. History will absolve me.” He was released in 1955 as part of an amnesty for political prisoners and lived in exile in the United States and Mexico, where he organized a guerrilla group with brother Raul and Ernesto “Che” Guevara, an Argentine doctor-turned-revolutionary. They named themselves the July 26 Movement, after the date of the failed Moncada attack.

In 1956, Castro and a few dozen rebels headed for Cuba aboard an old yacht called the “Granma.” Off course and long overdue, they beached the craft off the coast of Oriente province. Batista’s soldiers were waiting for them, and, again, most of Castro’s followers were killed.

The Castro brothers, Guevara and a handful of other survivors fled into the Sierra Maestra mountains along the nation’s southeastern coast, where they waged their guerrilla campaign against Batista.