This is a very different world than the one we have been living in since the dawn of the nuclear age. A world with multiple nuclear states, including some with revolutionary religious impulses or hegemonic ambitions, is a very dangerous place.

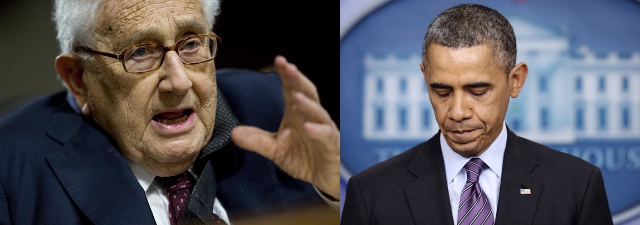

The former US Foreign Affairs Minister (Secretary of State) Henry Kissinger has warned the Barack Obama Administration a slack in the stance against Iran may lead the world into nuclear proliferation.

In the US-Iran controversy, which carries with it direct links to world oil prices, the Jewish American who worked as secretary of state at the peak of the East-West cold war in the 1970s has warned: “In the space of one year, that will create huge [nuclear] inspection problems…I’ll reserve my comment on that until I see the agreement. But I would also emphasize the issue of proliferation.

“Assuming one accepts the inspection as valid [and] takes account of the stockpile of nuclear material that already exists, the question then is what do the other countries in the region do? And if the other countries in the region conclude that America has approved the development of an enrichment capability within one year of a nuclear weapon, and if they then insist on building the same capability, we will live in a proliferated world….”

Henry Kissinger has made these remarks in a report published in the American business publication Wall Street Journal. The US-Iran controversy carries direct links to world oil prices as indicated in two of our earlier reports which included Iran’s struggle to survive crippling sanctions already in place. The Wall Street Journal report follows:

One big question coming out of the Munich security conference this weekend is whether Iran and the U.S. can strike a nuclear deal before the next, and perhaps final, deadline in March. But the better question may be what happens if they succeed—what happens if they sign an accord close to the parameters of the talks as we now know them? The Obama Administration may be underwriting a new era of global nuclear proliferation.

That’s the question Henry Kissinger diplomatically raised in recent testimony to the Senate that deserves far more public attention. The former Secretary of State is the dean of American strategists who negotiated nuclear pacts with the Soviets in the 1970s. This gives his views on the Iran talks particular relevance as President Obama drives to an accord that he hopes will be the capstone of his second term.

On Jan. 29, 2015, Mr. Kissinger appeared before the Senate Armed Services Committee with two other former Secretaries of State, George Shultz and Madeleine Albright. Here’s how he described the talks in his prepared remarks:

“Nuclear talks with Iran began as an international effort, buttressed by six U.N. resolutions, to deny Iran the capability to develop a military nuclear option. They are now an essentially bilateral negotiation over the scope of that capability through an agreement that sets a hypothetical limit of one year on an assumed breakout. The impact of this approach will be to move from preventing proliferation to managing it.” (The italics are Mr. Kissinger’s.)

Mull that one over. Mr. Kissinger always speaks with care not to undermine a U.S. Administration, and the same is true here. But he is clearly worried about how far the U.S. has moved from its original negotiating position that Iran cannot enrich uranium or maintain thousands of centrifuges. And he is concerned that these concessions will lead the world to perceive that such a deal would put Iran on the cusp of being a nuclear power.

Administration leaks to the media have made clear that Secretary of State John Kerry ’s current negotiating position is that Iran should have a breakout period of no less than a year. But as Mr. Kissinger told the Senators in response to questions, that means verification and inspections become crucial. “In the space of one year, that will create huge inspection problems, but I’ll reserve my comment on that until I see the agreement,” Mr. Kissinger said.

“But I would also emphasize the issue of proliferation. Assuming one accepts the inspection as valid” and “takes account of the stockpile of nuclear material that already exists, the question then is what do the other countries in the region do? And if the other countries in the region conclude that America has approved the development of an enrichment capability within one year of a nuclear weapon, and if they then insist on building the same capability, we will live in a proliferated world in which everybody—even if that agreement is maintained—will be very close to the trigger point.”

Mr. Kissinger didn’t say it, but those other nations include Saudi Arabia, which can buy a bomb from Pakistan; Turkey, which won’t sit by and let Shiite Iran dominate the region; Egypt, which has long viewed itself as the leading Arab state; and perhaps one or more of the Gulf emirates, which may not trust the Saudis. That’s in addition to Israel, which is assumed to have had a bomb for many years without posing a regional threat.

This is a very different world than the one we have been living in since the dawn of the nuclear age. A world with multiple nuclear states, including some with revolutionary religious impulses or hegemonic ambitions, is a very dangerous place. A proliferated world would limit the credibility of U.S. deterrence on behalf of allies. It would also imperil U.S. forces and even the homeland via ballistic missiles that Iran is developing but are not part of the U.S.-Iran talks.

President Obama would claim the inspection regime is fail-safe, but Iran hid its weapons program from United Nations inspectors for years. That’s why the U.N. passed its many resolutions and the current talks began. Iran also hid its facility at Qum. All of this shows how difficult it is to maintain a credible inspection regime in a country determined to evade it. Or as Mr. Kissinger delicately put it, “Nobody can really fully trust the inspection system or at least some [countries] may not.”

Our own view is that Mr. Obama is so bent on an Iran deal that he will make almost any concession to get one. In any case Mr. Kissinger’s concerns underscore the need for Congressional scrutiny and a vote on any agreement with Iran.