Next year will be mediocre at best as global markets stumble into a high-debt, low-investment environment.

By Peter Coy for Bloomberg, Published October 20, 2016.

There’s a scene in the 2004 movie Sideways where a sloppy, depressed Paul Giamatti gulps from the spit bucket at a wine-tasting bar. That’s probably worse than what International Monetary Fund chief economist Maurice Obstfeld had in mind when he said in October, while presenting the fund’s 2017 outlook, that “taken as a whole, the world economy is moving sideways.”

But there’s a sense among economists and chief executive officers that the developed economies in particular are drifting laterally—if not drunkenly—toward another year of mediocre growth at best.

Describing where the rich countries stand almost a decade after the worst financial blowup since the Great Depression, Obstfeld said: “The crisis has left a cocktail of interacting legacies—high debt overhangs, nonperforming loans on banks’ books, deflationary pressures, low investment, and eroded human capital—that continue to depress potential investment levels.”

The problem? Years of disappointing growth have caused the public to worry that this is the new normal and that governments and central bankers have no clue how to make it better. Pessimistic consumers are holding back on spending, while businesses aren’t putting money into buildings, equipment, or software. Their reticence slows things down even more. Disappointment breeds more disappointment.

That’s been the story for more than 20 years in Japan, where Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is struggling to root out deflationary psychology. It helps explain why voters in the U.K. rejected the advice of most economists and their prime minister and chose to exit the European Union. It accounts for the dwindling public support for free trade and open borders in continental Europe. And it explains the rise of Donald Trump, whose message is that the elites have failed the public.

In countries operating well below capacity, a crash program of infrastructure spending would generate growth and jobs in 2017. But voters won’t support increased spending if they distrust their leaders and focus on only the cost of projects and not their long-term benefits—clean water, safe bridges and tunnels, etc.

The U.S. is running closer to full capacity, but that hasn’t stopped many voters from embracing Trump’s message that ripping up trade deals and imposing punitive tariffs would boost growth and jobs. He says the U.S. should be able to grow at 4 percent or 5 percent a year, vs. 2 percent at present. The problem: A get-tough approach on trade might actually lower growth by raising the cost of imports and causing trading partners to retaliate with barriers to American exports.

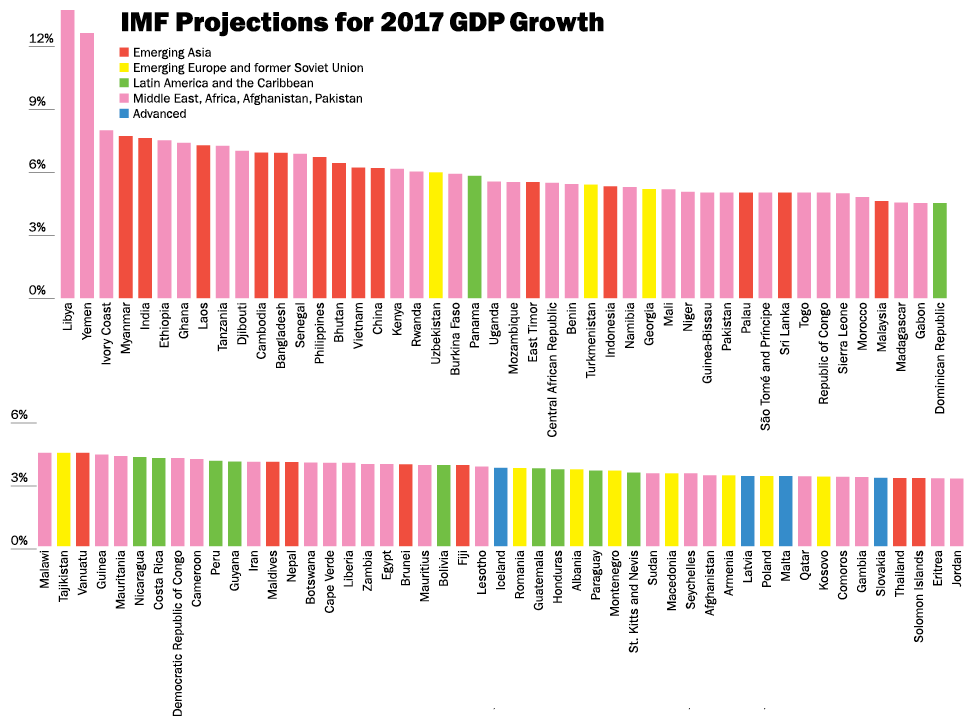

In many emerging markets, the outlook for 2017 is up, not sideways. India is headed for its third straight year as the fastest-growing major economy in the world, with the IMF projecting a 7.6 percent jump in gross domestic product. Helped by lower oil prices, the Reserve Bank of India has succeeded in bringing inflation down to about 5 percent a year from almost 11 percent as recently as 2013.

This year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi got lawmakers to pass a bankruptcy code that will speed up the resolution of insolvent companies, as well as a national sales tax that will ease interstate commerce by replacing a confusing jumble of state taxes. The tax is tentatively slated to take effect in April. India, soon to surpass China as the world’s most populous nation, is proof of what a country can achieve when it gets policy right. India still has plenty of problems, but for the moment, anyway, it seems to be better managed than the rich nations. “It’s unprecedented that emerging markets are perceived as having less political uncertainty than the advanced countries,” says Isabelle Mateos y Lago, chief multi-asset strategist at BlackRock Investment Institute.

China, whose economic takeoff preceded India’s, has a trickier management job, because its phase of hypergrowth is ending. The IMF projects 2017 growth of 6.2 percent, down from an estimated 6.6 percent this year. President Xi Jinping is trying to shift the economy toward consumer spending and away from corporate capital investment, infrastructure spending, and exports. That’s good for Asian nations that make goods that Chinese buy, bad for European, Japanese, and American companies that sell high-tech machines to Chinese manufacturers.

China, whose economic takeoff preceded India’s, has a trickier management job, because its phase of hypergrowth is ending. The IMF projects 2017 growth of 6.2 percent, down from an estimated 6.6 percent this year. President Xi Jinping is trying to shift the economy toward consumer spending and away from corporate capital investment, infrastructure spending, and exports. That’s good for Asian nations that make goods that Chinese buy, bad for European, Japanese, and American companies that sell high-tech machines to Chinese manufacturers.

The big question mark for China in 2017 is what Xi will do with the yuan, which recently fell to a six-year low. China must keep its value from free-falling to avoid another episode of panicky capital flight. But Xi, hoping to bolster the economy in advance of Communist Party elections in the fall of 2017, could be tempted to let the currency fall some more to gain a trade advantage—which would hurt the growth of trading partners.

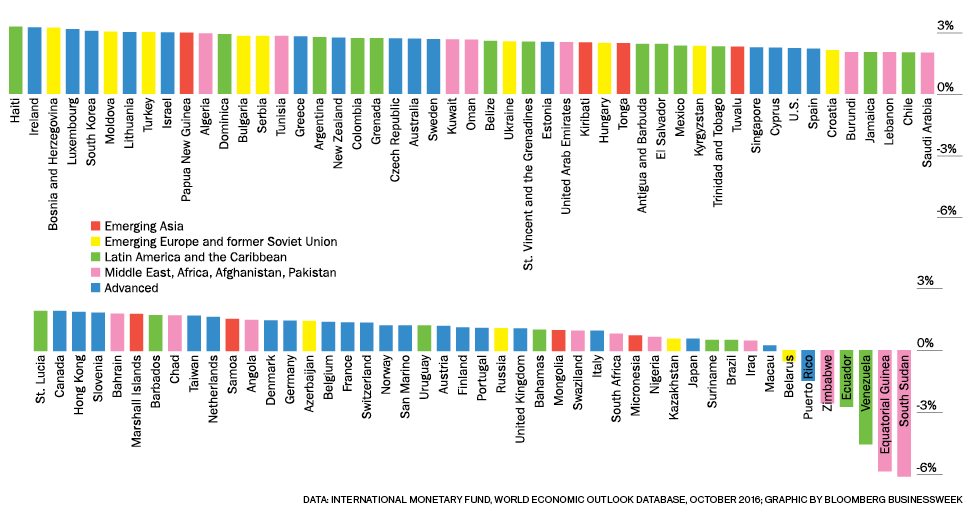

At least China has a master plan for taking its place on the world stage. The rich world is flailing, divided over what direction to take to restore growth and ensure that all parts of society share its fruits. The postwar consensus about the benefits of globalization has been shattered. The next president of the U.S., whether Trump or more likely Hillary Clinton, is publicly committed to reopening negotiations on the 12-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership. That could blow up the delicately constructed trade pact. The new year will tell whether British Prime Minister Theresa May continues to steer the U.K. toward a “hard” exit from the EU, which would sunder trade and investment ties as the price of gaining autonomy over immigration and regulation. The IMF in October halved its outlook for British growth in 2017, to 1.1 percent, citing Brexit turmoil.

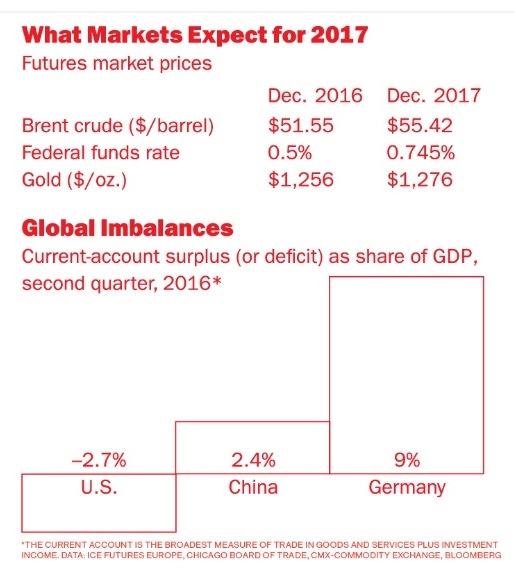

Also looming in 2017 are pivotal elections in France, where the right-wing populist Marine Le Pen is running for president, and Germany, which is likely to come under pressure to curb its outsize trade surpluses. German politicians tell other European countries not to stimulate their economies through government spending, but the country has been growing at the expense of those nations. In a world with more productive capacity than it needs, Germany’s excess of exports over imports forces plants to close in countries running trade deficits. Germany’s surplus in its current account in the second quarter of 2016 reached 9 percent of GDP. That drew a rebuke from Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi. “Stressing austerity means destroying Europe,” he told the Council on Foreign Relations in New York on Sept. 20. “Which is the only country which receives an advantage from this strategy? The one which exports the most: Germany.”

As the world’s largest economy and the buyer of last resort, the U.S. remains vital to the rest of the world. The IMF projects 2017 U.S. growth of 2.2 percent. The median forecast of economists surveyed by Bloomberg is also 2.2 percent. The highest forecast is 3.4 percent, from Parsec Financial Management, and the lowest is –0.4 percent, from Prestige Economics.

The Federal Reserve is assuming U.S. growth will be strong enough to justify three rate increases between now and the end of 2017. The federal funds rate should be just more than 1 percent at the end of 2017, according to the median projection of Fed voters. That may be optimistic. Investors, who have watched the Fed overestimate growth and interest rates year after year, are looking for the funds rate to get to less than 0.8 percent by yearend. “The engine of growth in the U.S. is sputtering,” warns Robert Johnson, president of the Institute for New Economic Thinking.

Continued soft growth should keep a lid on oil prices in 2017. In January the benchmark Brent crude fell below $28 a barrel. It hit $52 in October after OPEC agreed in principle on Sept. 28 to limit production, and Russian President Vladimir Putin said on Oct. 10 that his country would cooperate. But with global demand soft, there’s a glut of crude on the market that will make it hard for producers to resist the temptation to cut prices and compete for market share. The upshot is that futures markets are looking for Brent to finish 2017 slightly higher than where it is now. Gold, a hedge against inflation and political turmoil, is projected by markets to stay roughly even in 2017 at under $1,300 an ounce.

Global trade this year and next is forecast to grow at the slowest pace since the financial crisis. Disillusionment is taking hold. “The division is between people who think the future is a place of hope and the people who think it’s a trap,” Italy’s Renzi said during his New York visit. Says Columbia Business School Dean Glenn Hubbard: “We run the risk of slow growth turning into a crisis.”