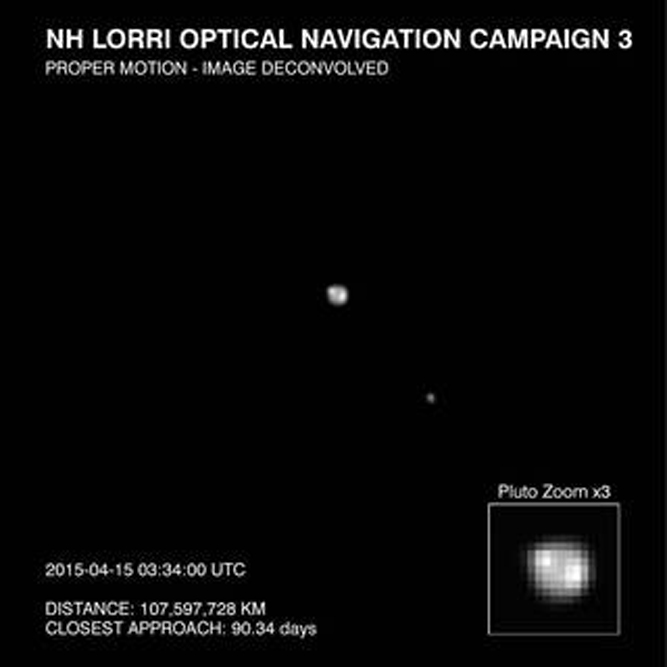

NASA’s New Horizons Detects Surface Features, Possible Polar Cap on Pluto. This image of Pluto and its largest moon, Charon, was taken by the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) on NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft on April 15, 2015. The image is part of several taken between April 12-18, 2015 as the spacecraft’s distance from Pluto decreased from about 69 million miles (93 million kilometers) to 64 million miles (104 million kilometers). Photo Credits: NASA/JHU-APL/SwRI

The surface of Pluto, the last planetary object on our solar system is finally visible. Pictures of Pluto taken by the American spacecraft New Horizons from 70 million miles away have revealed bright and dark regions of the planetary object and what scientists believe may be a polar cap.

In another development, the US space exploration agency, NASA, says the spacecraft MESSENGER sent to study the planet Mercury slammed into Mercury’s surface at about 8,750 mph and created a crater on the planet’s surface the week that ended April 25, 2015.

Modern technology has in the meantime made it possible for scientists to see further and deeper into our galaxy—the Milky Way galaxy –where the sun that gives us energy is only one of the stars.

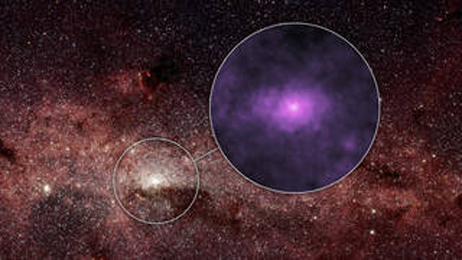

Peering into the heart of the Milky Way galaxy, NASA’s Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (NuSTAR) has spotted a mysterious glow of high-energy X-rays that, according to scientists, could be the “howls” of dead stars as they feed on stellar companions.

“We can see a completely new component of the center of our galaxy with NuSTAR’s images,” said Kerstin Perez of Columbia University in New York, lead author of a new report on the findings in the journal Nature. “We can’t definitively explain the X-ray signal yet — it’s a mystery. More work needs to be done.”

ABOUT THE NEW IMAGES FROM PLUTO MISSION

The images were captured in early to mid-April from within 70 million miles (113 million kilometers), using the telescopic Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) camera on New Horizons. A technique called image deconvolution sharpens the raw, unprocessed images beamed back to Earth. New Horizons scientists interpreted the data to reveal the dwarf planet has broad surface markings – some bright, some dark – including a bright area at one pole that may be a polar cap.

“As we approach the Pluto system we are starting to see intriguing features such as a bright region near Pluto’s visible pole, starting the great scientific adventure to understand this enigmatic celestial object,” says John Grunsfeld, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. “As we get closer, the excitement is building in our quest to unravel the mysteries of Pluto using data from New Horizons.”

Also captured in the images is Pluto’s largest moon, Charon, rotating in its 6.4-day long orbit. The exposure times used to create this image set – a tenth of a second – were too short for the camera to detect Pluto’s four much smaller and fainter moons.

Since it was discovered in 1930, Pluto has remained an enigma. It orbits our sun more than 3 billion miles (about 5 billion kilometers) from Earth, and researchers have struggled to discern any details about its surface. These latest New Horizons images allow the mission science team to detect clear differences in brightness across Pluto’s surface as it rotates.

“After traveling more than nine years through space, it’s stunning to see Pluto, literally a dot of light as seen from Earth, becoming a real place right before our eyes,” said Alan Stern, New Horizons principal investigator at Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. “These incredible images are the first in which we can begin to see detail on Pluto, and they are already showing us that Pluto has a complex surface.”

The images the spacecraft returns will dramatically improve as New Horizons speeds closer to its July rendezvous with Pluto.

“We can only imagine what surprises will be revealed when New Horizons passes approximately 7,800 miles (12,500 kilometers) above Pluto’s surface this summer,” said Hal Weaver, the mission’s project scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland.

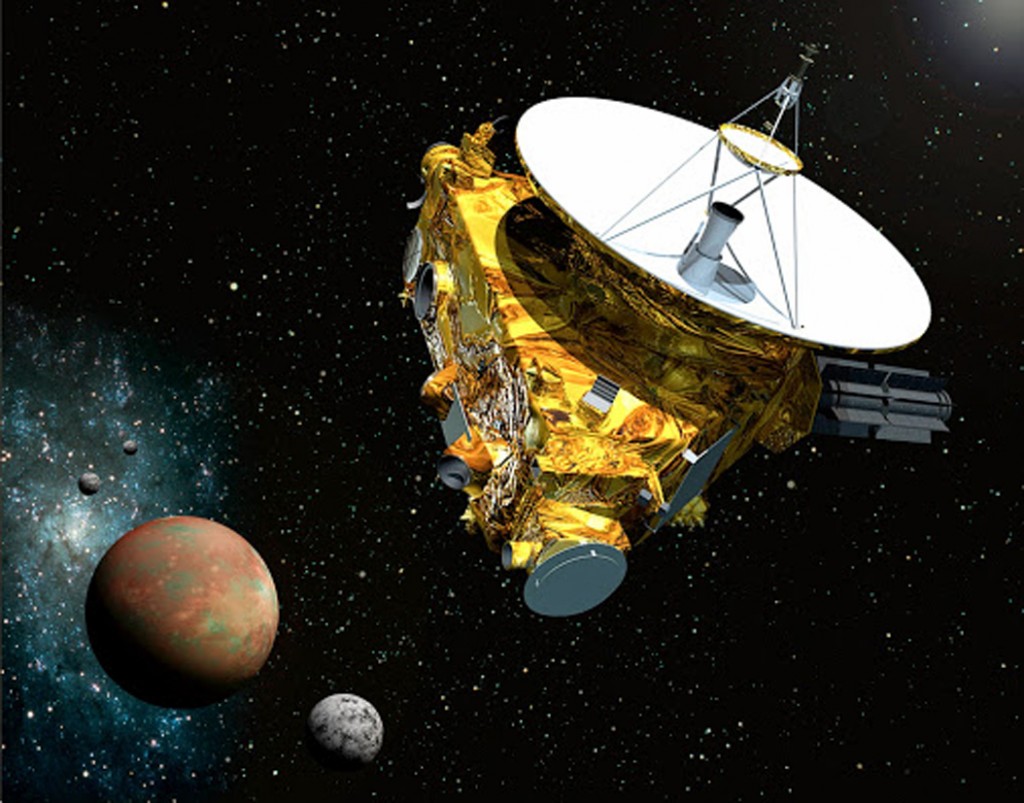

APL designed, built, and operates the New Horizons spacecraft, and manages the mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. SwRI leads the science team, payload operations and encounter science planning. New Horizons is part of the New Frontiers Program managed by NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

ABOUT THE ‘SUICIDE MISSION ‘ TO MERCURY

A NASA planetary exploration mission came to a planned end, but nonetheless dramatic, on Thursday, April 30, 2015, when the mission spacecraft MESSENGER slammed into Mercury’s surface at about 8,750 mph and created a new crater on the planet’s surface.

Mission controllers at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, have confirmed NASA’s MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging (MESSENGER) spacecraft impacted the surface of Mercury, as anticipated, at 3:26 p.m. EDT.

Mission control confirmed end of operations just a few minutes later, at 3:40 p.m., when no signal was detected by NASA’s Deep Space Network (DSN) station in Goldstone, California, at the time the spacecraft would have emerged from behind the planet. This conclusion was independently confirmed by the DSN’s Radio Science team, which also was monitoring for a signal from MESSENGER.

“Going out with a bang as it impacts the surface of Mercury, we are celebrating MESSENGER as more than a successful mission,” said John Grunsfeld, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. “The MESSENGER mission will continue to provide scientists with a bonanza of new results as we begin the next phase of this mission–analyzing the exciting data already in the archives, and unravelling the mysteries of Mercury.”

Prior to impact, MESSENGER’s mission design team predicted the spacecraft would pass a few miles over a lava-filled basin on the planet before striking the surface and creating a crater estimated to be as wide as 50 feet.

Mercury’s lonely demise on the small, scorched planet closest to the sun went unobserved because the probe hit the side of the planet facing away from Earth, so ground-based telescopes were not able to capture the moment of impact. Space-based telescopes also were unable to view the impact, as Mercury’s proximity to the sun would damage optics.

MESSENGER’s last day of real-time flight operations began at 11:15 a.m., with initiation of the final delivery of data and images from Mercury via a 230-foot (70-meter) DSN antenna located in Madrid, Spain. After a planned transition to a 111-foot (34-meter) DSN antenna in California, at 2:40 p.m., mission operators later confirmed the switch to a beacon-only communication signal at 3:04 p.m.

The mood in the Mission Operations Center at APL was both somber and celebratory as team members watched MESSENGER’s telemetry drop out for the last time, after more than four years and 4,105 orbits around Mercury.

“We monitored MESSENGER’s beacon signal for about 20 additional minutes,” said mission operations manager Andy Calloway of APL. “It was strange to think during that time MESSENGER had already impacted, but we could not confirm it immediately due to the vast distance across space between Mercury and Earth.”

MESSENGER was launched on Aug. 3, 2004, and began orbiting Mercury on March 17, 2011. Although it completed its primary science objectives by March 2012, the spacecraft’s mission was extended two times, allowing it to capture images and information about the planet in unprecedented detail.

During a final extension of the mission in March, referred to as XM2, the team began a hover campaign that allowed the spacecraft to operate within a narrow band of altitudes from five to 35 kilometers from the planet’s surface.

On Tuesday, the team successfully executed the last of seven daring orbit correction maneuvers that kept MESSENGER aloft long enough for the spacecraft’s instruments to collect critical information on Mercury’s crustal magnetic anomalies and ice-filled polar craters, among other features. After running out of fuel, and with no way to increase its altitude, MESSENGER was finally unable to resist the sun’s gravitational pull on its orbit.

“Today we bid a fond farewell to one of the most resilient and accomplished spacecraft to ever explore our neighboring planets,” said Sean Solomon, MESSENGER’s principal investigator and director of Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in Palisades, New York. “A resourceful and committed team of engineers, mission operators, scientists, and managers can be extremely proud that the MESSENGER mission has surpassed all expectations and delivered a stunningly long list of discoveries that have changed our views–not only of one of Earth’s sibling planets, but of the entire inner solar system.”

Among its many accomplishments, the MESSENGER mission determined Mercury’s surface composition, revealed its geological history, discovered its internal magnetic field is offset from the planet’s center, and verified its polar deposits are dominantly water ice.

APL built and operated the MESSENGER spacecraft and managed the mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington.IN

MYSTERIOUS, ‘ZOMBIE’ STARS IN MILKY WAY– OUR GALAXY

Peering into the heart of the Milky Way galaxy, NASA’s Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (NuSTAR) has spotted a mysterious glow of high-energy X-rays that, according to scientists, could be the “howls” of dead stars as they feed on stellar companions.

“We can see a completely new component of the center of our galaxy with NuSTAR’s images,” said Kerstin Perez of Columbia University in New York, lead author of a new report on the findings in the journal Nature. “We can’t definitively explain the X-ray signal yet — it’s a mystery. More work needs to be done.”

The center of our Milky Way galaxy is bustling with young and old stars, smaller black holes and other varieties of stellar corpses – all swarming around a supermassive black hole called Sagittarius A*.

NuSTAR, launched into space in 2012, is the first telescope capable of capturing crisp images of this frenzied region in high-energy X-rays. The new images show a region around the supermassive black hole about 40 light-years across. Astronomers were surprised by the pictures, which reveal an unexpected haze of high-energy X-rays dominating the usual stellar activity.

“Almost anything that can emit X-rays is in the galactic center,” said Perez. “The area is crowded with low-energy X-ray sources, but their emission is very faint when you examine it at the energies that NuSTAR observes, so the new signal stands out.”

Astronomers have four potential theories to explain the baffling X-ray glow, three of which involve different classes of stellar corpses. When stars die, they don’t always go quietly into the night. Unlike stars like our sun, collapsed dead stars that belong to stellar pairs, or binaries, can siphon matter from their companions. This zombie-like “feeding” process differs depending on the nature of the normal star, but the result may be an eruption of X-rays.

According to one theory, a type of stellar zombie called a pulsar could be at work. Pulsars are the collapsed remains of stars that exploded in supernova blasts. They can spin extremely fast and send out intense beams of radiation. As the pulsars spin, the beams sweep across the sky, sometimes intercepting the Earth, like lighthouse beacons.

“We may be witnessing the beacons of a hitherto hidden population of pulsars in the galactic center,” said co-author Fiona Harrison of the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena, and principal investigator of NuSTAR. “This would mean there is something special about the environment in the very center of our galaxy.”

Other possible culprits include heavy-set stellar corpses called white dwarfs, which are the collapsed, burned-out remains of stars not massive enough to explode in supernovae. Our sun is such a star, and is destined to become a white dwarf in about five billion years. Because these white dwarfs are much denser than they were in their youth, they have stronger gravity and can produce higher-energy X-rays than normal. Another theory points to small black holes that slowly feed off their companion stars, radiating X-rays as material plummets down into their bottomless pits.

Alternatively, the source of the high-energy X-rays might not be stellar corpses at all, astronomers say, but rather a diffuse haze of charged particles, called cosmic rays. The cosmic rays might originate from the supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy as it devours material. When the cosmic rays interact with surrounding, dense gas, they emit X-rays.

However, none of these theories match what is known from previous research, leaving the astronomers largely stumped.

“This new result just reminds us that the galactic center is a bizarre place,” said co-author Chuck Hailey of Columbia University. “In the same way people behave differently walking on the street instead of jammed on a crowded rush hour subway, stellar objects exhibit weird behavior when crammed in close quarters near the supermassive black hole.”

The team says more observations are planned. Until then, theorists will be busy exploring the above scenarios or coming up with new models to explain what could be giving off the puzzling high-energy X-ray glow.

“Every time that we build small telescopes like NuSTAR, which improve our view of the cosmos in a particular wavelength band, we can expect surprises like this,” said Paul Hertz, the astrophysics division director at NASA Headquarters in Washington.

NuSTAR is a Small Explorer mission led by Caltech and managed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington.