By Jaston Binala, Recently in Mang’ula, Kilombero.

Morogoro Region in eastern Tanzania is mostly rich agricultural land producing everything from rice and maize to lettuce, from beans to bananas, cow peas to tree tomatoes.

Morogoro is also famous for its tropical forests on slopes of the Udzungwa mountains, where foreign tourists hike and trek as they watch a rare species of red monkeys on their way to a hidden waterfall up the mountain forest.

The spectacular splendour hides a painful story, however, on the eastern side of the Udzungwa mountains– a story of failure where a once thriving industrial complex created to manufacture railway machinery and automotive spare parts has been reduced to farmland with a failed English medium primary school owned by the St. Mary’s International Schools chain .

The transformation of Mang’ula Mechanical and Machine Tools complex into the wasted capital that it is at the moment is result of a faulty privatization process.

The English medium school at Mang’ula is known to belong to the nominated Member of Parliament, the Rev. Dr. Getrude Rwakatare, who declined to be interviewed despite repeated requests over a four-week waiting period during which several interviews were promised but never came through.

The industrial complex operated a foundry warehouse, forging fabrication, heat treatment and carpentry; a prefabricated concrete manufacturing plant (PCM) which had nine warehouses; administration buildings, including dormitories and three hospital buildings. The complex occupied slightly less than 200 acres of land.

Mang’ula Mechanical and Machine Tools complex was built at the eastern foot of the Udzungwa ranges in 1969–a few kilometres from the famous Kilombero Sugar factory. Set on what was originally a remote rice farming village called Mang’ula, the complex was built with Chinese assistance to manufacture spare parts for equipment used in the construction of the Tanzania Zambia Railway (TAZARA) between 1970 and 1975, as well as the manufacture of automotive spare parts.

The complex initially comprised of a prefabricated concrete manufacturing plant, a saw mill and a mechanical engineering workshop. TAZARA, also known as Uhuru Railway line, was completed in 1975–two years ahead of schedule.

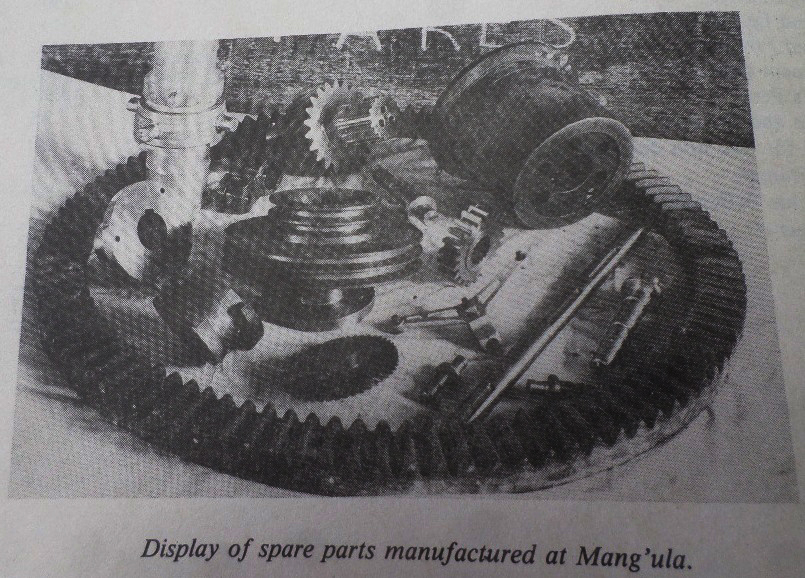

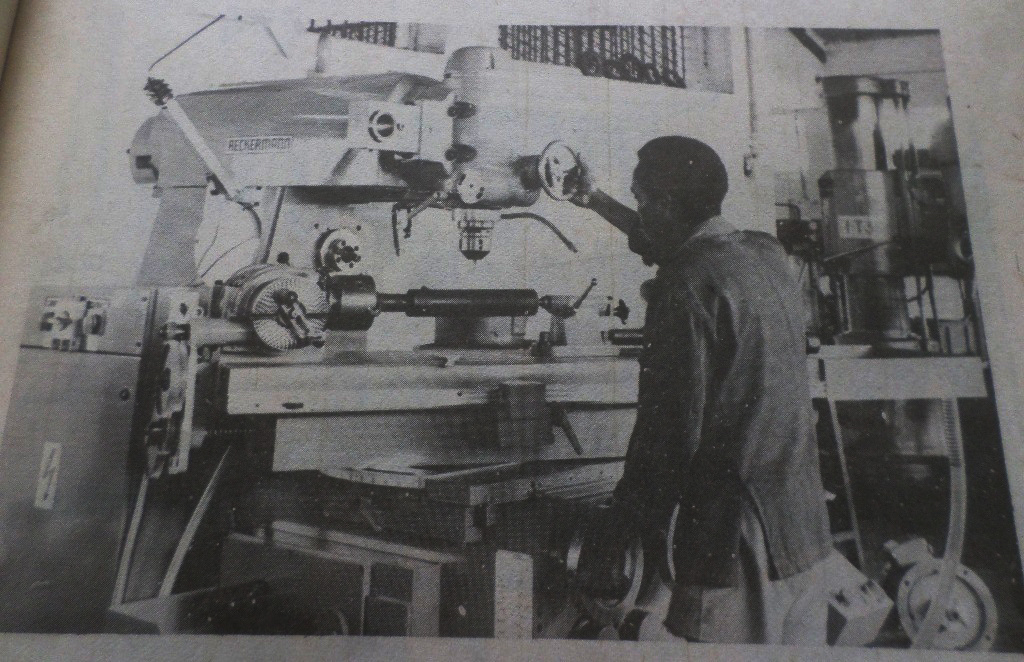

Records at Tanzania’s National Development Corporation (NDC) show the mechanical engineering section of the complex was in 1977 transformed from a light engineering workshop into a heavy, commercial engineering plant producing everything from railway and motor vehicle spare parts to rice hullers, maize mills, coffee pulpers, sorghum hullers and water pumps.

In the year 1977 the mechanical engineering section was valued at the equivalent of USD 3.0 million (computed from its 1977 known value of Tsh. 23.9 million/- by applying the exchange rate of Tsh 7.96 per USD at the time), according to open data available at the original holding company, the State owned National Development Corporation (NDC).

The mechanical engineering section which became Mang’ula Mechanical and Machine Tools Limited (MMMT) was sold in a privatization plan to the Tanzanian company St Mary’s International Schools on February 27, 2007 at a property value equivalent of USD 473,933 (Tsh. 600 million) at the 2007 exchange rate but only USD 292,259 (Tsh, 370 million) was actually paid. It is not clear why only a small portion of the amount was paid at the time.

A local governments official, Adam Bakari Sungura–elected Ward Councillor by residents of Mang’ula A in the Kilombero district where the complex is located–said the privatized MMT was now an English medium primary school pretending to be an engineering college.

The local government at Mang’ula had understood that St Mary’s International Schools had entered into a contract with the Tanzania Government through the Ministry of Industry, Trade and Investments in which the private investor was supposed to continue plans for which the complex was created in 1969 and later improved in 1977, and that it was also asked to establish a technical college.

The investor established a technical college only in writings on the walls and not in practice; the company started running an English medium school instead.

An independent investigation funded by the China-Africa Industrial Reporting Project and Thomson Reuters Foundation found the Mang’ula complex part bush and part tilled land prepared for cultivation of peas, rice, maize, beans and bananas.

And the public may never come to know who should take responsibility for the transformation of this heavy commercial engineering complex with potential to continue employing local people and contributing to the national economy from what was, from what it was meant to be, into a small, failing English medium primary school.

The cause of the apparent destruction of Mang’ula Mechanical and Machine Tools complex– located slightly more than 300 kilometres west of Tanzania’s business capital, Dar es Salaam– is hidden in hard to crack secrecy.

Alley Mwakibolwa, a former senior employee at the plant when it was still operational, said this was the biggest railway and automobile spare parts manufacturing plant in eastern and central African in the 1970s. Mwakibolwa does not recall the exact number of employees at this time but he estimates in 1982 the engineering plant provided 73 direct full time staff jobs and 35 part time jobs. The figures consist of management staff, stores, procurement, foundry shop, machine-shop and fabrication staff.

The first car engine to be produced in east and central Africa was built here between 1980 and 1981, Mwakibolwa testifies. The saloon car engine was taken to State House in Dar es Salaam to be shown to Tanzania’s first President Mwalimu Julius Nyerere for him to see the industrial capacity the Chinese had brought to Tanzania. Mwalimu saw the car engine. Mwalimu heard the roar of the engine, and he was amazed, Mwakibolwa said.

The desk officer in charge of industrial affairs at the Ministry of Industry, Trade and Investment, Elli Palangyo, referred this reporter to the Permanent Secretary in the Ministry for any answers on questions relating to MMMT. The questions were sent to the Permanent secretary who in turn referred this reporter to the Treasury Registrar at the Ministry of Finance. A response letter from the Ministry of Industry, Trade and Investment dated 19 May, 2017 signed by Obadiah Nyagiro reads in part: “Contact the Treasury Registrar. This is the authority on all matters concerning state enterprises which were privatized.”

On 11 July, 2017 the then Treasury Registrar at the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning, Dr. Oswald Mashindano responded to questions in a letter marked ‘Confidential’:

“This office wishes to inform you that the asset disposal agreement entered between the Government and the investor contains a confidentiality clause which prohibits any one party to divulge information without consent of the other party. Therefore…it is good that you contact the buyer [of the Mang’ula complex]—St. Mary’s International Schools for consent. The office of the Treasury Registrar will give all the co-operation needed upon receiving the investor’s consent.”

It was not immediately possible to identify an Act of the law in Tanzania which provides for the sale of public enterprises to be confidential.

No signs of a heavy industrial manufacturing plant existed in January and March 2017 when this reporter visited the complex. The administration block had been transformed into classrooms and dormitories, but the school could not get enough pupils to fill up the block in order to make it ‘a going concern,’ Sungura, the local politician, said.

This reporter found what was in the past the foundry warehouse, the forging fabrication, heat treatment and carpentry areas, the prefabricated concrete manufacturing plant (PCM) where a number of warehouses still stood were all surrounded by tall weeds and what looked like a banana plantation and land tills prepared for either maize, rice or beans farming; and an occasional goat would cross the fields.

Railway tracks running into an area which linked the manufacturing complex to the Tanzania Zambia Railway (TAZARA) railway line about half a kilometre away was vandalized; steel railways tracks had been uprooted and missing. One section had only one steel track line remaining while a concrete water well appeared covered by water lilies and green algae.

A source speaking on condition of anonymity said the machines which were in the past used in the manufacturing process—including lathe machines— and which were still functional when the complex was handed over to the private investor, had been uprooted and sold to a Kenyan entrepreneur as scrap metal.

It was not possible to confirm this report, but the uprooting of the Mang’ula machinery would be reminiscent of what happened at the the Ubungo Farm Implements (UFI) factory: Machines used in the manufacture of agricultural machinery were uprooted and sold to a Kenyan company as scrap metal, but the Kenyan company is reported to have painted and resold the machinery at exorbitant price and the machinery was re-commissioned to produce agricultural machinery.

St Mary’s International Schools refused this reporter permission to visit the foundry warehouse, the forging fabrication building, the heat treatment and carpentry area and the nine warehouses and the administration block in January 2017. It was therefore not possible to establish the value of the missing machinery.

Mang’ula Mechanical and Machine Tools Company comprises of a vast area, most of it sitting idle for lack of use. The apparent neglect of the complex in 2008 attracted the attention of villagers who quickly turned the eastern part of the complex into farmland.

St. Mary’s International Schools instituted a court case number 40/2008 at the Ifakara Land Disputes Court in 2008 to stop the encroachment, arguing the entire area of the industrial complex had been sold. The court ruled in the school’s favour, the head of the school said over a telephone interview, refusing to divulge his name.

Separately, some 75 workers the School had fired after inheriting them from the Government had not been paid their salaries and terminal benefits during the course of reporting for this story. The workers filed a lawsuit in 2016 against St. Mary’s International Schools to demand settlement. The labour dispute was still unresolved at the time or writing this story.

“The project is too big for the kind of investor that it was given to,” Sungura, a politician in his early 30s said. “The school does not take students from the local community either, because its school fees are prohibitive and even those that come from elsewhere are few. And they appear to be picked for the sake of filling up classes.”

The Government sold the railway spare parts and automobile parts manufacturing complex for a reduced price on the condition the investor transform it into a mechanical engineering college for the whole country but which would benefit young people in the surrounding communities the most.

The Investor has never conducted engineering courses, Sungura, the local governments official, complained. Ironically, an engineering training organization called PLAN saw opportunity at the Mang’ula area. Working with the Tanzania Vocational Training Institute (VETA), a government vocational training set-up, PLAN started short term training courses at different premises at Mang’ula town.

The ward councillor said the PLAN program trains young people welding, motor vehicle mechanical engineering including fixing motorcycles, sewing and cookery.

Officials present at Mang’ula Mechanical and Machine Tools in January 2017, including head of the English medium primary school who refused to divulge his name in a telephone interview, provided the telephone number used by the owner of Tanzania’s St. Mary’s International Schools, the Rev. Dr. Getrude Rwakatare, also a nominated member of the Tanzania Parliament and lead Pastor at a large congregation church in Dar es Salaam called ‘KANISA LA MLIMA WA MOTO MIKOCHENI’.

The mobile phone number on the Tanzania Tigo network carrier was not picked on several calling attempts. The mobile phone number was later removed from the network.

At KANISA LA MLIMA WA MOTO MIKOCHENI an assistant to the Lead Pastor identified as Ndugu Kibona said the Rev. Dr. Rwakatare had agreed to talk to this reporter because there was nothing to hide, adding that he would call when she would be available for the meeting. Ndugu Kibona never called as the reporter waited in Dar es Salaam for four weeks between February and March 2018. The promised face to face interview with the owner of St. Mary’s International Schools never materialized.

Numerous State owned enterprises under NDC were poorly managed and ended up being privatized by the Parastatal Sector Reform Commission (PSRC), a commission formed specifically to privatize failed state enterprises as Tanzania’s economy was being transformed from a command socialist economy into a free market economy in the 1990s.

Like most State-owned enterprises from the socialist era, the history of Mang’ula Mechanical and Machine Tools Limited (MMMT) is riddled with poor financial management and politically charged management methods devoid of economic sense.

Mwakibolwa recalls, for instance, that it was originally planned that the foundry be built at Mchuchuma area in Southern Tanzania–an area known to have a huge reservoir of iron ore and which was also within vicinity of the TAZARA railway. The move want meant to locate a huge foundry where it would be close to the iron ore.

Some politicians disputed the idea demanding a foundry must be built close to Mt. Kilimanjaro. The concept of a large foundry close to the iron ore at Mchuchuma disappeared, giving birth to construction of the Mang’ula foundry and Kilimanjaro Machine Tools some six kilometres west of Moshi town.

Political intrigue continued to plague MMMT, leading to poor productivity until the foundry was declared economically worthless. Coopers and Lybrand audited the Mang’ula 1977/1978 books of accounts. The financial reports available at NDC today show the auditors discovered theft as at December 31, 1978.

“No provision had been made in the accounts in respect of the amount of Tsh. 132,000/- shown in the balance sheet as a loan due to the company. In our opinion this amount is doubtful recovery,” the auditors reported. “Debtors stated at Tsh. 3,637,000/- include amounts due from former directors of Tsh. 197,279. No provision has been made for these debts which in our opinion are doubtful of recovery.” Signed – Coopers and Lybrand.

PSRC had a timeline to complete privatization of the worthless State owned enterprises after which it would be wound up, albeit leaving a number of privatization issues unresolved as it stopped operations. Its activities were later given to a new government entity formed to deal with privatization-related problems. The activities were transferred to the also now defunct Consolidated Holding Corporation (CHC) in 1997.

Some 274 state enterprises had been privatised by 2012, according to official data which says CHC audited 170 of these privatised firms to check if privatization terms of reference were being adhered to. The data published in 2013 found 42 of these enterprises were making profit, 70 were loss-making while 58 were not operational at all.

The reports say on June 4, 2011, the Mang’ula Mechanical and Machine Tools investor told a project audit committee a new plan existed to revive the business by turning it into a polytechnic college. But the investor was already known to have a history of investing mainly in non-technical schools. Investigators also found no evidence of goodwill to develop the complex.

CHC found that despite the fact that the company had potential to survive for another 100 years, it was found in a rundown condition with a large part of its buildings neglected. In 2015, the Treasury Registrar said owners of some privatized factories and facilities had breached terms for which they were privatized.

Speaking in Tanga region recently, President John Pombe Magufuli of Tanzania admitted “we made mistakes in the past when we privatized factories”. He ordered the Minister for Industries, Trade and Investment to repossesses all factories which have not adhered to the original privatization plan; the failed privatized state industries.

The Minister for Industries, Trade and Investment, Mr. Charles Mwijage swung into action following this order. He identified eight factories for repossession on claims investors had failed to comply with privatization requirements. Mang’ula Mechanical and Machine Tools Company Ltd is on the list.

The MMMT story is therefore not an isolated incident. Recent project audits found major deviations from privatization terms of reference at the agricultural products packaging company Unga Limited in Arusha Tanzania and at the tea packing factory in Tanga region, Mponde Tea Factory. One source asking for anonymity said a textile company privatized to continue producing textiles in Dar es Salaam has been found to deal in motorcycle assembling instead of textiles manufacturing.

On Thursday, April 5, 2018, Gerald Chami, the Treasury Registrar’s Head of Communications said the Treasury Registrar had completed a final Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) of Mang’ula Mechanical and Machine Tools Company Limited (MMMT) and some action is to be taken after relevant authorities have read the report, but he said contents were still confidential. He showed a copy of the new M&E report to this reporter but insisted it was top secret.

So the Government is taking some action on the wasted complex but one major question will be demanding a good answer: who should be held responsible for this waste?

This story was produced by TZ Business News. It was written as part of Wealth of Nations, a Pan-African media skills development programme run by the Thomson Reuters Foundation. More information at www.wealth-of-nations.org