The independent media, which includes internet outlets, is construed to threaten the grip on power for many African autocracies.

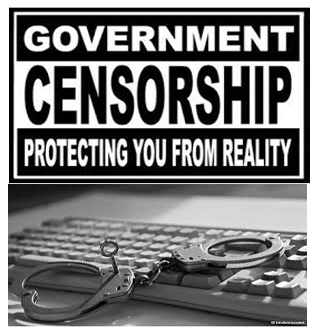

Tanzania recently passed through parliament the Cyber Crime Act and the Statistics Act with clauses which criminalize many journalistic activities done in the public interest.

Eritrea is the most censored country in the world, according to a list of 10 countries where the press is most restricted; the list was compiled by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). And while Tanzania does not appear on this list, the East African nation has recently enacted two laws which bring it closer to the 10 listed dictatorships on the question of freedom of the press, according to analysts.

Tanzania recently passed through parliament the Cyber Crime Act and the Statistics Act with clauses which have criminalized many journalistic activities done in the public interest. Analysts have highlighted areas in the acts which will work against the proffession of journalism at the following link:CRUEL SECTIONS IN THE CYBER LAW (UNTRANSLATED KISWAHILI ANALYSIS).

The CPJ list is based on research into the use of tactics ranging from imprisonment and repressive laws to harassment of journalists and restrictions on Internet access. In Eritrea, President Isaias Afewerki has succeeded in his campaign to crush independent journalism, creating a media climate so oppressive that even reporters working for state-run news outlets live in constant fear of arrest.

The threat of imprisonment has led many journalists to choose exile rather than risk arrest in their country. Eritrea is Africa’s worst jailer of journalists, with at least 23 behind bars, none of whom has been tried in court or even charged with a crime.

Eritrea scrapped plans in 2011 to provide mobile Internet for its citizens, limiting the possibility of access to independent information. Although Internet is available, it is through slow dial-up connections, and fewer than 1 percent of the population goes online, according to U.N. International Telecommunication Union figures.

Eritrea scrapped plans in 2011 to provide mobile Internet for its citizens, limiting the possibility of access to independent information. Although Internet is available, it is through slow dial-up connections, and fewer than 1 percent of the population goes online, according to U.N. International Telecommunication Union figures.

Eritrea also has the lowest figure globally of cell phone users, with just 5.6 percent of the population owning one. The tactics used by Eritrea and North Korea are mirrored to varying degrees in other heavily censored countries.

To keep their grip on power, repressive regimes use a combination of media monopoly, harassment, spying, threats of journalist imprisonment, and restriction of journalists’ entry into or movements within their countries.

In Ethiopia—the number four country on CPJ’s most censored nations list–the threat of imprisonment has also contributed to a steep increase in the number of journalists fleeing into exile. Amid a broad crackdown on bloggers and independent publications in 2014, more than 30 journalists were forced to flee, CPJ research shows.

Ethiopia’s 2009 anti-terrorism law, which criminalizes any reporting that authorities deem to “encourage” or “provide moral support” to banned groups, has been the basis used against many of the 17 journalists in jail there.

The independent media, which includes internet outlets, is construed to threaten the grip on power for many African autocracies, analysis has shown.

In May, 2015, which is a couple of days ago, Ethiopians went to the polls in the country’s fifth general election since the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front came to power more than 20 years ago.

Citizens were expected to choose the right party to lead them for the next five years through information available to them through the independent media. To elect the right candidates to Government office, Ethiopians needed to have a clear understanding of their country’s political, social, and economic situation.

They needed to know which parties have the candidates and policies best suited to their own hopes and aspirations. But in this country with limited independent media, many Ethiopians struggled to find the information needed to help them make informed decisions.

The election was held on Sunday May 24, 2015. Today there is already an outcry from the opposition. Ethiopia’s main opposition party has condemned the elections, which saw the ruling party cruise back into office, as a “disgrace” and proof the country was a one-party state.

According to preliminary results from the Sunday elections, the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) of Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn secured all 442 parliamentary seats so far declared on Saturday, May 30, 2015) out of the 547 seats up for grabs. Did the people lack information on candidates?

A number of human right reports showed 2014 as the most dangerous year for the Ethiopian press, with government attacks on the media starting a year before the election.

It appeared that government forces were purposely clearing the media out of the way. Seventeen journalists are currently in prison, most of them facing terrorism charges, and more than 30 have been forced into exile, according to CPJ research. This makes Ethiopia the second-worst jailer of journalists in Africa, after Eritrea.

Five independent magazines and one weekly newspaper were charged last year with publishing false information, inciting violence, and undermining public confidence in the government, according to CPJ research. The charges highlighted the narrowed media space, and led to the closure of several more outlets out of fear that they may face the same fate.

Ethiopia is the fourth most censored country in the world, according to CPJ. Besides state-run publications, only a handful of privately owned publications remain in the country and, according to a couple of Ethiopian journalists, the outlets operate under heavy self-censorship.

Because of financial constraints caused by the paper and printing costs, nearly all independent publications circulate only in the capital, Addis Ababa. This leaves the majority of the population dependent on the state-run TV and radio stations.

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reports that in Egypt, newspapers and internet news outlets are targeted by the government for harassment. Egyptian authorities recently arrested the editor-in-chief of the privately owned weekly El-Bayan for allegedly “publishing false news which would disturb public security, spread terror among citizens and harm the public interest,” according to news reports.

The trouble with the Egyptian Government’s subjective conclusion leading to the detention of the El-Bayan journalist is that he was detained without a court verdict. Authorities said Aref was arrested because El-Bayan posted an article on its website that alleged six prosecutors had been killed on the Cairo-Suez road, according to one news website. But deaths had indeed occurred, according to reports.

The paper’s editorial board issued a statement on El-Bayan‘s website, retracting the article and asking the prosecutor-general to show them leniency and release Aref. The Editor in Chief was released on bail.

“In the event that journalists or news outlets make a mistake, there should be plenty of means of redress that do not involve throwing someone in prison,” said Sherif Mansour, CPJ’s Middle East and North Africa program coordinator. “Furthermore, criminal accusations against a journalist are unlikely to solve any genuine security problems facing Egyptian authorities.”

The Egyptian Journalists Syndicate criticized the arrest and said that the press law does not provide for preventive detention in cases related to publishing and that Aref’s arrest was illegal because the syndicate had not been informed beforehand, reports said.

CLAMPDOWN IN BURKINA FASO

In Burkina Faso, the High Council for Communication–the media regulatory body known as le Conseil superieur de la Communication–declared a three-month suspension on live political broadcasts aired by TV and radio stations, according to a statement on its website dated May 12, 2015. The statement said the order went into effect on May 7.

The country is being ruled by a transitional government until the elections. The three month suspension has come after President Blaise Compaore was forced to step down from office in October 2014. Compaore had sought to alter the country’s constitution to allow him to seek re-election in 2015, but was met with a series of protests in October 2014,according to news reports.

“This blanket suspension by Burkinabe authorities amounts to outright censorship,” said Peter Nkanga, CPJ’s West Africa representative. “If authorities care to hold a credible election this year, they must allow media outlets to resume broadcasting live political debate.”

The council said “serious violations” had been observed during live broadcasts, but did not identify the stations that had allegedly violated the rules and did not specify the violations committed.

Authorities in Burundian have attacked news outlets in recently weeks to muzzle the free media. At least five radio stations were attacked during violence over an attempted coup in the capital, Bujumbura, and threats were made against a newspaper which caused it to stop publishing, according to reports.

The attacks occurred after several weeks of protests and civil unrest following President Pierre Nkurunziza’s announcement on April 25 of his intention to seek a third term in office at elections which were scheduled for June 26, 2015, but which have now been disrupted by the political instability in Burundi.

Major General Godefroid Niyombare announced on a privately owned radio station that he was deposing the president, according to news reports. Supporters of the president and Niyombare both began demonstrating in the streets, and the protests turned violent. The president, who was in Tanzania at the time the coup was announced, returned to Burundi, according to reports.

Unidentified individuals fired grenades into the compounds of privately owned stations Bonesha FM, Renaissance Radio and Television, Radio Isanganiro, and the privately owned Burundian station African Public Radio, according to reports.

Another report said the offices of African Public Radio had been burned down, with reports saying that it had been hit by a rocket. None of the stations are currently operating. In Burundi, where Internet penetration was only 1.3 per cent in 2013 according to the International Telecommunications Union, the radio is the primary source of news.

Iwacu, Burundi’s most widely circulated newspaper, posted on Twitter on Thursday that it too had shut down. According to Human Rights Watch, the paper closed after receiving threats that it would be targeted in the same way as the radio stations if it continued publishing.

Web users trying to access Iwacu’s website on Friday were greeted with a message that said the paper had been forced to temporarily stop work because of safety reasons.

Armed supporters of President Nkurunziza and Niyombare fought for control of state-run radio Burundi National Radio and Television (RTNB), reports said. Pro-government forces had succeeded in forcefully regaining control of the station, reports said. The state broadcaster is a particularly powerful news outlet because it is the only station that broadcasts nationally, news reports said.

Protesters attacked the privately owned pro-government radio station Rema FM. Some news reports said the station was burned down. Other reports said cars in front of the station were set on fire, but the station had not been destroyed.

Mélanie Gouby, a French freelancer who is in Burundi, told CPJ that social networking sites including Twitter, WhatsApp, and Facebook had been temporarily inaccessible on cell phones, but she said the Internet had not been cut at any point during the past few days. Blocked mobile access to social media platforms was likely a move intended to prevent Burundians from using the platforms to organize further gatherings and protests, according to reports