Industrialized countries argue for free trade, but most have high tariff barriers for manufactured and processed goods from Africa. However, industrial countries insist that African countries open up their markets to both agricultural and manufactured goods from industrial countries.

By William Gumede, for Third World Network Features.

Global market rules are either in favour of, or are frequently bent to benefit industrial countries. Or, to put it differently, more restrictive market rules are often applied to African countries while industrial countries are accorded leeway to implement these in ways that benefit their companies, labour and economies.

The first of these is that industrial countries have more power to determine the rules of the market than African and other developing countries.

Many industrial countries following the 2007/2008 global and Eurozone financial crises nationalized failing banks, but if African countries try to do so, they will face restriction and criticism from markets, global media and financial institutions.

Many industrial countries, for example, can come up with monetary policies to ostensibly improve their export competitiveness, such as artificially keeping the value of their currencies and interest rates low. The US, the EU and Japan have been doing this for years.

In the aftermath of the 2007/2008 global and Eurozone financial crises the US, because interest rates there were already close to zero, introduced quantitative easing (QE), the strategy of injecting money directly into the country’s financial system. QE is printing new money electronically and buying government bonds, which increases the circulation of money, in order to boost consumer and business spending.

Such unilateral monetary policies have undermined the competitiveness of African countries by causing seesawing capital flows, currency volatility and destabilization of financial markets.

African countries do not have the economic power to introduce their own quantitative easing – and even if they had, there are likely to be market, investor and industrialized-country backlashes against them.

Industrialized countries argue for free trade, but most have high tariff barriers for manufactured and processed goods from Africa. However, industrial countries insist that African countries open up their markets to both agricultural and manufactured goods from industrial countries.

Industrial countries frequently have non-tariff barriers such as high quality, health and environmental standards for products coming from African countries. African countries do not have the same freedom to enact similar non-tariff barriers for products coming from industrial countries.

Furthermore, industrial countries heavily subsidize their own sensitive industries, such as agriculture. Yet, African countries are punished when they want to protect their own infant or sensitive industries. The US Africa Opportunity Act (AGOA) or the EU Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs), for example, allow US and EU governments to subsidize their strategic industries; but both the US and EU forbid African countries to do the same, or they will lose out on “benefits” from AGOA and the EPAs.

Industrial countries insist that African countries allow multinational companies unfettered investment freedom in African economies, often with disregard for the local environment, labour standards or good corporate governance. Again, if African countries do not allow the free entry of industrial country goods, they are likely to face market, investors and industrialized-country political backlashes.

The international currency in which trade takes place is either the US dollar or other industrialized-country currencies, such as the Euro, British Pound or the Japanese Yen. The raw materials that most African countries export to industrial countries are usually traded in these currencies. Fluctuations in these currencies impact disproportionally on African economies, particularly because the economies are heavily dependent on the export of one commodity.

The prices, exchanges and bourses of all African commodities are set in industrial countries. This means that, astonishingly, African producers, even where they are the global dominant producers of a specific commodity, have no say in the price of that commodity.

In the global market, labour from industrial countries can move freely to African countries; yet African labour movement to industrial countries is increasingly restricted. The arguments for free markets ring hollow, without the free movement of labour.

Industrial countries also control the supporting structures of global markets: the credit rating agencies, transport and logistics, insurance agencies and the banks and the global communications systems.

Industrial countries dominate global transportation, insurance and finance markets, needed to export African products. Major global credits rating agencies are controlled by industrial countries and are often biased against, lack knowledge of, or generalize about African economies on a one-size-fits all basis.

Global markets are increasingly underpinned by communications technology, with trading, financing and business done digitally. Industrial country companies dominate communications technology.

The global public institutions that support global markets are all controlled by industrial countries, their appointees and their dominant views. Some of these include ‘public’ global institutions such as the US- and European Union-led World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and its private sector affiliate, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), and the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

African countries proportionally lose more through international tax rules that favour industrial countries and allow multinational companies great leeway to practice tax avoidance, illicit trade and profit shifting in African countries. As Rob Davies, the South African Trade and Industry Minister, said rightly “changing international tax rules and closing loopholes which facilitate and enable international tax evasion and aggressive avoidance” are only dealt with by the Organisation for Economic Development and Cooperation (OECD), which most African and developing countries are not members of.

African countries must push for such global issues, which impact directly on them, to be handled through multilateral intergovernmental mechanisms.

African countries must push for global public institutions that support global markets such as the World Bank and IMF to give them a greater say in decision-making.

African countries must forge better coalitions to push for the improvement of the governance of global markets, allow individual African countries with the same policy space to ‘govern’ markets. African countries must as a bloc introduce appropriate industrial, development and trade policies. This will make it more difficult for industrialized countries, global public institutions and global markets to punish individual African countries for policies that industrial countries implement but are not punished for.

African countries should then introduce the very same economic policies – if appropriate – that industrial countries implement, but which are seen by industrial countries, global markets and supporting public and private institutions as anti-market.

For more than half a century since the end of colonialism, of the 54 African countries, arguably only two have ever come up with an industrial policy on the scale of South Korea, Taiwan or Singapore. African governments, leaders and civil society groups have more often than not come up with criticisms (rightly so) of how industrialized countries and global public and private market institutions and markets undermine African development.

But African governments, leaders and civil society groups have often never come up with pragmatic, well-thought out development policies, beyond slogans, such as “return the land”, or “return the mines”, or “nationalize foreign companies”. What is needed are detailed industrial plans, using a country’s talents, empowering the largest number of people, and using the best of what industrial countries and other developing countries are doing as long as it is appropriate to the African context.

African countries must also pool their own resources to create, in partnership with other developing countries, alternative, fairer and more equitable global public institutions because current ones are dominated by industrialized countries.

African producers of commodities must attempt to set up coordinating agencies, like the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), for the commodities they produce, in order to have a bigger influence in determining the prices of those commodities.

Our countries must diversify their products, and move away from overwhelmingly depending on commodity exports. They must also add value to their commodities by producing manufactured and processed products.

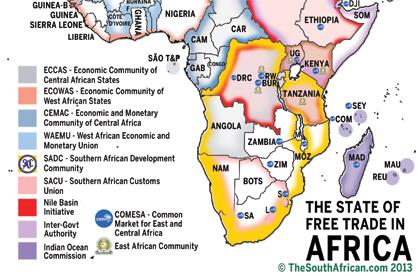

African countries must pool their markets and genuinely begin to trade with each other. They must introduce industrial policies to diversify their markets away from industrial countries.

But African leaders and governments must govern their countries better – poor governance further weakens their power against global public institutions, markets and industrialized countries. Source: Sunday Observer.