The total value of Africa’s trade with the world topped $1.1 trillion in 2014, compared to $597 billion in 2010, according to the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)…. Africa’s trade with the EU totaled $374 billion in 2014, $54 billion of it with the UK, [exporting $27 billion in goods and services to the UK].

By JAKE BRIGHT for This is Africa.

The UK’s decision to leave the European Union in the June 2016 referendum shocked international markets, which experienced notable volatility in the days after the vote.

Through a process outlined by the Article 50 of the EU’s Lisbon Treaty, the UK will negotiate its EU withdrawal over a period of up to two years.

There are still many unknowns, but many forecasts including the IMF’s have predicted downward trending growth for the EU, a pending UK recession, and a depreciating pound. As politicians determine the technicalities of Britain’s departure – known as Brexit – widespread speculation continues as to what the ripple effects will be.

There are plenty of questions on what it could mean for Africa’s core economies.

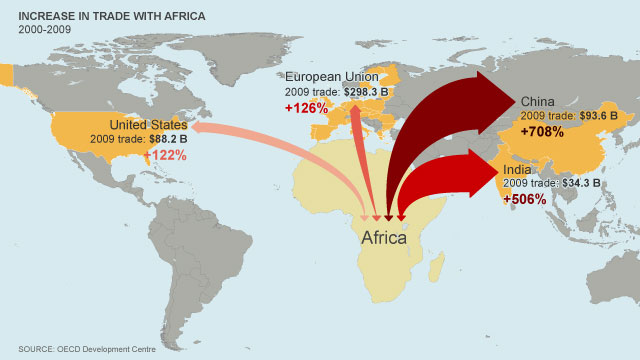

Over the last decade, sub-Saharan Africa has gone from being one of the world’s least connected regions when it comes to commercial channels to rapidly increasing its share of global trade, investment, and financial flows.

[Now, months] after Brexit, This is Africa takes a look at potential impacts on business and investment across Africa.

Curbing exports

The total value of Africa’s trade with the world topped $1.1tn in 2014, compared to $597bn in 2010, according to the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

Africa’s trade with the EU totaled $374bn in 2014, $54bn of it with the UK. It exported $27bn in goods and services to the UK alone.

Brexit’s main impact on African trade could be fewer exports from “all Sub-Saharan Africa sovereigns” with “close trade ties with the UK and EU,” according to a brief by Moody’s, the ratings agency.

“There is a possibility for reduced growth in the UK and EU, which in part will then reflect itself in reduced demand for imports from African countries,” says Moody’s senior analyst Zuzana Brixiova.

“There is a possibility for reduced growth in the UK and EU, which in part will then reflect itself in reduced demand for imports from African countries,” says Moody’s senior analyst Zuzana Brixiova.

According to Ms Brixiova, Brexit’s overall impact on regional growth could be negligible. “[Exports] to UK countries represent less than 1 percent of GDP for all sub-Saharan African countries,” she points out.

The two sub-Saharan African countries with the highest percentage of GDP from exports to the UK are South Africa (1.2 percent) and Mauritius (2.7 percent). While Nigeria is the UK’s second largest African trading partner in volume, its exports to the UK account for only 0.4 percent of its GDP.

Two countries stand out as most exposed to a Brexit-induced slowdown in the EU however. The Republic of the Congo, for which trade with the EU accounts for 20.1 percent of GDP, and Côte d’Ivoire, at 11.9 percent of GDP, stand to be the worst affected.

Another Brexit effect is uncertainty around trade provisions. The EU has entered into severalEconomic Partnership Agreements with African countries that reduce duties and tariffs on certain goods.

However, after Brexit many of these EPAs will have to be renegotiated, notes Atlantic Council senior Africa fellow Aubrey Hruby. “Without the UK involved they could be less meaningful and their benefit to African exports less certain.”

The future of Kenya’s cut flower exports to the EU is one example. Currently flowers can be shipped to the EU tariff free per the terms of a 2014 EPA. The UK is the second largest destination for these flowers after the Netherlands.

After Brexit, Kenya could face costlier conditions on flower exports until the UK negotiates a separate trade deal, as well as a decline in demand if the UK enters recession.

Currency fluctuations

Since Brexit, sterling has plummeted and the US dollar has strengthened. Exchange rates play a significant role in pricing, supply, and demand for exports between countries.

A continued decline in the value of the pound and euro could make African exports to the UK and EU more expensive, and therefore reduce demand.

These trends have already come together to cost Kenyan fruit growers $79,000 a day since the Brexit vote. This illustrates the potential losses to produce exporters who pay for freight in dollars but receive payments for their goods in pounds.

Remittances could also feel the knock on effects of Brexit. Since 2010, Africans living abroad have remitted more money annually than the continent’s entire official development assistance budget of $57bn. The diaspora remitted $64bn in 2015 alone.

The UK is the fourth largest source of remittances to Africa, accounting for flows of $5.2bn in 2015. These could drop if the pound continues to lose value.

The possibility that post-Brexit UK immigration policy would allow fewer work permissions for Africans from large countries, such as Nigeria, could also reduce remittance flows.

Shifting markets

Africa has been connecting rapidly to global capital markets. Nile Fund manager Larry Seruma predicts that the region’s total stock market capitalisation will have doubled from its 2015 value to roughly $2.2tn by 2017.

The leading sub-Saharan African exchanges by value and listed companies are South Africa with a market capitalisation of $1.01tn and 397 listings, followed by Nigeria ($80bn, 184 listings), and Kenya ($20bn, 65 listings).

Mr Seruma does not see Brexit ripples significantly impacting Nigeria or Kenya’s exchanges. However “South Africa is different,” he says. “Some dual listed [South African] corporates are headquarted in London, but doing business in Europe – this will change going forward.”

A number of these dual listed companies, such as mining major Anglo-American and financial services group Old Mutual, could relist and relocate their European headquarters, Mr Seruma believes.

He also sees Brexit shifting the priority of African companies looking to go public. “London Stock Exchange (LSE) listings will be become less desirable with Britain outside the EU,” he says.

This could sway a number of pending African IPOs, including the $1bn LSE listing of Nigerianfintech company Interswitch later this year.

Sovereign bonds have also become an increasingly active financing channel for African governments.

Sub-Saharan Africa issued $18bn in dollar-denominated eurobonds between 2013 and 2015, more than triple the amount in the preceding three years combined. This included many first time offerings.

Brexit raises questions of increased borrowing costs for African governments at a time when many are struggling to plug growing deficits. Most if not all yields on these are serviced in dollars and increase with perceived market risk.

Moody’s Ms Brixiova sees other global economic factors having a greater impact on Africa’s sovereign bonds – particulary commodity price shocks. “I am not saying I do not see any risks to repayment…but Brexit is a minor factor in the greater scheme of possible shocks as they relate to [Africa’s] eurobonds,” she says.

Samir Gadio, Standard Chartered’s head of Africa strategy, points to Africa’s external government bonds are actually performing better since Brexit.

“The markets are now pricing that the US Federal Reserve is less likely to hike its interest rate and that has actually triggered a rally…African names have performed well,” Mr Gadio notes.

“We have reached the lowest spreads on the region this year.”

This may be complicated on the back of stronger jobs numbers, which prompted the Fed to state it was open to a rate hike later this year on 27 July.

Foreign investment, global uncertainty

Foreign direct investment (FDI) to Africa reached $54bn in 2016, nearly double its 2005 total of$29bn. The UK mirrors this trend. Its FDI stock in Africa nearly doubled from $40bn in 2005 to $70bn 2014, according to Moody’s.

Brexit related uncertainty and a possible UK recession could delay investment decisions and reduce UK investment flows to the continent. “There are push and pull factors,” says Ms Brixiova. “On the pull side it depends on…what kind of business environment and sectors become attractive to investors.”

She points to South Africa’s economy as most at risk from a decline in UK-Africa investment. The UK is South Africa’s largest source of FDI, accounting for 46 percent of the country’s FDI stock in 2014.

Brexit’s chilling effect on the global economy could also play a role in overall FDI flows to Africa, according to Amadou Sy, senior fellow at the Brookings Institute.

“It has to do with how risky the business environment will be globally,” he says. “If people are more risk averse in general investors will likely forego some investment in Africa, which is perceived to be a higher risk environment.”

Turning inwards

In 2015, the UK’s development assistance budget was $18bn. Africa was the largest beneficiary, receiving $2.54bn.

The UK remains the only country in the G7 group of rich nations to have enshrined its commitment to spend 0.7 percent of gross national income (GNI) on aid every year, honoring its UN commitments. A Brexit-induced slowdown in the UK economy would shrink this number.

Currently the UK’s aid to Africa flows through both bilateral channels and multilateral institutions. A substantial portion of it goes to the European Development Fund (EDF), of which the UK is the largest contributor. The UK financed 14 percent ($565m) of EDF’s 2014 budget.

After Brexit, presumably all of the UK’s EDF funding would end. There is also uncertainty on the future of the UK’s development policies.

Rhetoric on British isolationism were a prominent feature of pro-Brexit political campaigns. Mr Sy at Brookings thinks that the “end of British outwardness” as signalled by Brexit could impact the UK’s development policies across Africa.

The three largest recipients of bilateral UK development assistance are Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone, which each receive more than $200m annually. In many African economies any significant reduction in aid can adversely impact GDP.

“With an end of outwardness the UK will say, we care most about domestic policies. In that case it could affect fragile and low income countries in Africa,” he posits.

The British exit from the EU throws up some tricky questions for African leaders who, under the auspices of the African Union, have been moving in the opposite direction – namely, pushing towards an African common market and policies.

“A lesson from Brexit for African leaders is the critical [importance] of communicating to citizens the benefits of integration…beyond the short term costs,” says Mr Sy.

Ultimately, however he does not believe the EU’s challenges will discourage the project of African regional integration. “We have so much to gain from the free movement of people, capital, goods, and digital information.” Source: This is Africa.